PCC’s Randy Lee honored for national co-op contributions

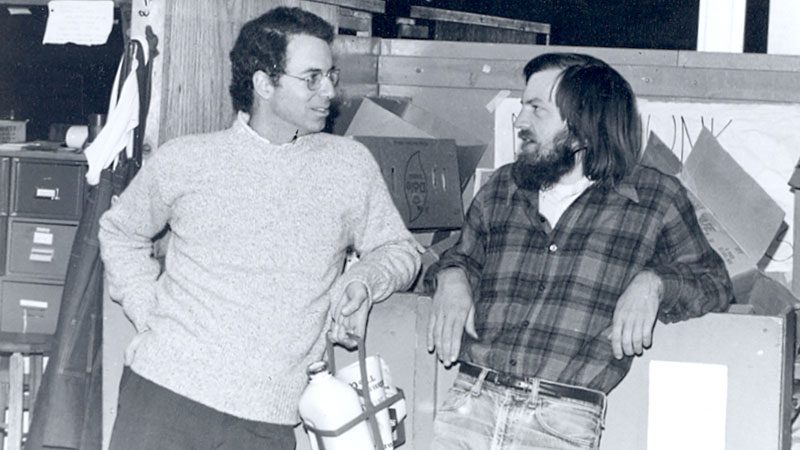

The future of PCC changed forever at a routine board meeting in 1970. Printed minutes from that meeting note a guest observer: Randy Lee.

Lee wasn’t there to talk about groceries. A former University of Washington student who had recently returned to town, he was a young community organizer with some economics classes under his belt and an interest in co-ops.

A surprise job offer after a subsequent staff meeting led Lee to a 47-year career with PCC, where he helped steer the co-op from a single quirky storefront into the largest member-owned grocery in the country. He retired as PCC’s Chief Financial Officer in 2018.

Without Lee, a 1995 staff tribute noted, PCC as we know it wouldn’t exist — and PCC might not exist at all.

Lee, once praised by a store manager as having “the mind of an accountant and the heart of a poet,” will be inducted into the National Co-operative Hall of Fame for his contributions to both PCC and to co-ops nationwide. The ceremony is scheduled for Oct. 9 at the National Press Club in Washington D.C.

A steady hand and collaborative leader at PCC, Lee also made “a pretty huge impact” in strengthening the power of cooperatives across the nation, said Jeff Voltz, the co-op’s CEO from 1992 to 2000.

“We’re cooperators. We spread the credit around. But (Lee) I think is a big contributor to what exists today.”

Co-ops as an organizing tool

Lee had returned to Seattle in 1970 after a stint with the U.S. National Student Association in Washington D.C., then with the U.S. Student Government Association in Chicago, where he was connected with Saul Alinsky’s Industrial Areas Foundation, working on community organizing.

Settling back into Seattle, he moved into a group house with old friends in Montlake, Lee recalled in a recent interview. One roommate cooked meals in lieu of rent, shopping at PCC for macrobiotic ingredients.

Lee visited the store, which was then on 65th street in the Ravenna neighborhood. “I was pretty much put off by the food they had,” he joked – carob and tofu. But he believed cooperatives would be an interesting tool for organizing: “It’s pulling people in a community together for economic power.”

Discussions at the board meeting included the need for an assistant store manager. A day or two later, Lee got a call asking if he was interested. He needed to pay rent and said sure.

His lack of experience wasn’t an issue. It was “plug in” and learn how to run the cash register, how to mark prices, how to fill a barrel with an 100-pound bag of bulk goods without throwing out his back. A few months later, when the store manager left, Lee more or less automatically moved into that role.

Lee thinks his biggest influence over PCC’s path came at that point: “It was bleeding red ink. It was in serious financial trouble. And the dismaying thing to me was that nobody… knew what a balance sheet was. Well, they must have known what it was, but we had balance sheets that didn’t balance.”

The 1995 PCC tribute noted that finances were so bad when Lee arrived that vendors were demanding cash payments — some were accidentally paid twice — and health department visits “were more like raids.”

Instead of turning him off, the potential engaged him. “This could be so much better, so easily. Just do the obvious,” he thought.

Lee downplays his contributions — “it was good people coming together to do good things that complemented each other” — but his vision and steady, (mostly) quiet leadership was crucial throughout the decades.

Lee shifted the co-op from a heavily volunteer staff to a paid workforce, making a PCC job a profession rather than a sometimes-erratic hobby. He cut his own pay to help bring up workers compensation and benefits. Still in his 20s, he was trying to “move towards an organization that could support grown-ups living lives with partners and children.” He earned the confidence of vendors and the respect of the health department, the 1995 writeup said, and began weekly all-staff meetings that “became the culture in the yogurt of what we call democratic management,” its governance system at the time.

People called the store “the food co-op” or just “the co-op,” Lee encouraged them to call it by name – Puget Consumers Co-op, at the time, or PCC for short.

Helping a co-op grow

Lee joined up at a turning point in PCC’s mission. It had recently moved from Madrona to Ravenna, and was shifting from its original purpose, a buying club aimed at saving money, to a co-op encouraging health and nutrition and environmental justice. Located near the University of Washington, at a time when such issues were fueling a national movement, the co-op attracted a younger and passionate clientele.

(“That was back when there was a skull and crossbones emblem on the sugar,” noted Voltz.)

As PCC’s finances strengthened, it loaned money to other co-ops in the region to help them get established or grow stronger. Then came another fundamental shift: A prospective Eastside co-op had requested substantial PCC assistance, but “the finances that they were able to put together didn’t cut it,” Lee said.

Instead, the membership voted to buy the assets of “Co-op East” in Kirkland and open it as a second PCC store, seeding the multi-branch co-op of today.

“It wasn’t a vision or a sophisticated plan, for sure, but it… just made more sense,” Lee said. Individual neighborhood co-ops didn’t have the power of a united organization, and didn’t benefit from any economies of scale. Lee focused on the bottom line along with ideals.

“That’s the message that I perhaps brought to the co op the most, that this is going to be a business first, and a co op second. I want it to be a great co-op, but it cannot be anything without being a great business.”

Lee’s logic, and the accompanying investments, backed some inspiring endeavors, from cooking classes and nutrition fairs to local laws and national organic standards. Lee’s signature is preserved on the first receipt for vegetables sold by Cascadian Farm, a tiny and aspirational organic farm in the early 1970s, now a global organic giant. Founder Gene Kahn once told Sound Consumer how “Even when I showed up with ugly, very improperly washed carrots, Randy would take them. They were so flexible because they were full of empathy and respect for what we were trying to do.”

Nancy Taylor, who worked for PCC for 32 years before retiring as vice president of human resources in 2019, said Lee “was true to the ideals of the cooperative, and really made decisions, always, with that in mind.”

A steady and analytical steward of co-op resources, Taylor said, Lee could also step back and look at the big picture of how decisions would impact PCC — and other organizations. A good listener and a good mentor, he knew when to lend support, and when other ventures could move forward on their own.

For instance, when PCC member Darlyn Rundberg suggested saving a farm in danger of development, turning it into a “P-Patch” of community garden plots in 1973, PCC paid staff member Koko Hammermeister to oversee what ultimately became a citywide treasure.

The cost was low — a part-time staffer’s time — and the commitment would benefit the membership. There was no thought that the gardens would compete with PCC sales, Lee said — produce was not the year-round powerhouse that it is today, and, beyond that, if the gardens were beneficial to the membership, that meant they benefited the co-op. “There’s no demographic difference between people who garden at a P-Patch and people who will shop at our store.”

And when the PCC Farmland Fund (now the Washington Farmland Trust) was launched in 1999 to save an endangered organic farm, Lee said the same thinking applied: “This would be very good. This has possibilities” – not just for the single property at risk of development, but for the bigger picture of what members valued. Lee served on the Farmland Trust’s board for 19 years.

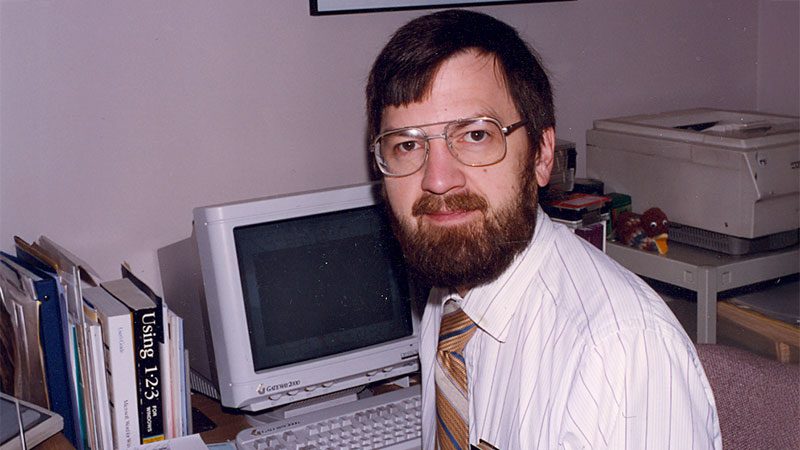

Over his tenure, Lee became a store financial coordinator and then the co-op wide CFO. He had never received his undergraduate degree from the University of Washington — with that era’s “cynical attitude toward higher education, I said I want the education but I don’t care about the degree,” he said. He left his senior year with three incompletes. But in the mid-1980s, he recalled, then-PCC manager Lyle Whiteman got support from the Board of Trustees to send Lee to the University of Washington’s Executive MBA program.

“That’s such a big thing in my life. It chokes me up a little bit,” Lee said. “It was so important for my career, getting the financial training that was so far beyond any I’d had in just undergraduate economics classes.”

It helped PCC navigate upheavals in the grocery industry, including once-unimaginable competition from global corporations entering the market for organic and natural foods and products.

PCC steadily expanded under Lee’s watch, to 12 stores by his retirement (including the 1990s opening and closing of the ill-fated South Everett store.)

“It was unheard of to grow the way that we did,” Taylor said. Food co-ops were traditionally a single store, or two at the most. It took major realignments to successfully grow into a larger organization, and it carried major responsibilities.

“We took it really seriously,” Taylor said, realizing “all these people’s jobs depend on us.”

Along the way, Lee helped solve the structural problem he’d identified in the 1970s, that co-op grocery stores could become more powerful and sustainable if they banded together.

The start of National Co+op Grocers

Lee was a leader in establishing the National Cooperative Grocers Association (now National Co+op Grocers) in 1999, uniting food co-ops around the country to negotiate better buying power and other coordinated national services. NCG credits Lee, who served on the board for nearly two decades and contributed to a major 2004 reorganization, with establishing its national purchasing program.

“I suppose it’s not too unlike how PCC got to (expand to) more stores. It’s just scale. It was really fundamentally scale. How could we do more?…” Lee said. A major catalyst was a meeting in Seattle with a half-dozen or so of the major co-ops, including Walden Swanson, who worked on co-ops for long-term planning.

Lee said his contribution was probably supporting PCC’s investment in the organization – with its multiple stores, PCC had the funds that the smaller co-ops didn’t.

“It became fairly large, fairly quickly. I don’t remember any big (push) for additional members, because it had such a huge potential payoff. Let’s buy together. Everybody’s out there on an island by themselves.”

More than a CEO

Lee never sought the top job at PCC, though he served as interim co-op CEO at times and worked as co-leader in the 2010s with former CEO Tracy Wolpert.

A CEO position wouldn’t have been a good fit, he said. Soft spoken and not particularly extroverted, “I see my strengths as being supportive of people,” making the organization stronger without the burdens and baggage of the executive’s position.

But with the job — and PCC — evolving over the decades, Taylor said Lee’s role went far beyond and above the typical CFO’s position. The continuity of his presence meant a lot.

“He was the glue in a lot of ways, as well as a leader.”

One of Lee’s most influential decisions, as it happened, was related to that top job. He served on the committee that hired Cate Hardy as PCC’s CEO in 2015. “It’s actually one of the most proud tasks I had. It’s up there in the ones I enjoyed the most and I thought were most impactful for PCC in the later part of my life.”

Hardy, a former Starbucks executive, brought PCC “what none of us had already,” Lee said — the perspective that came from a much larger company.

“She was working internationally as well as nationally, so she saw scale, and she saw a lot of things go wrong.” Having seen those things made it easier to avoid a repeat.

Hardy could see where the co-op was lagging and where it could shine. To make that impact, she hired other leaders who could have opted for big-time jobs at major companies offering higher compensation than a food co-op could. “These people would come on board, and they would be excited about it. That’s not very visible for people outside, but it was huge inside,” Lee said.

That story, like so much else about the co-op work, just emphasized that “the whole story” is about other people, not any one individual, he said.

It reaffirmed to him that he had been in the right job all along: “I just loved doing that kind of work of making this organization, not just bigger per se, but better.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated since it was originally published.