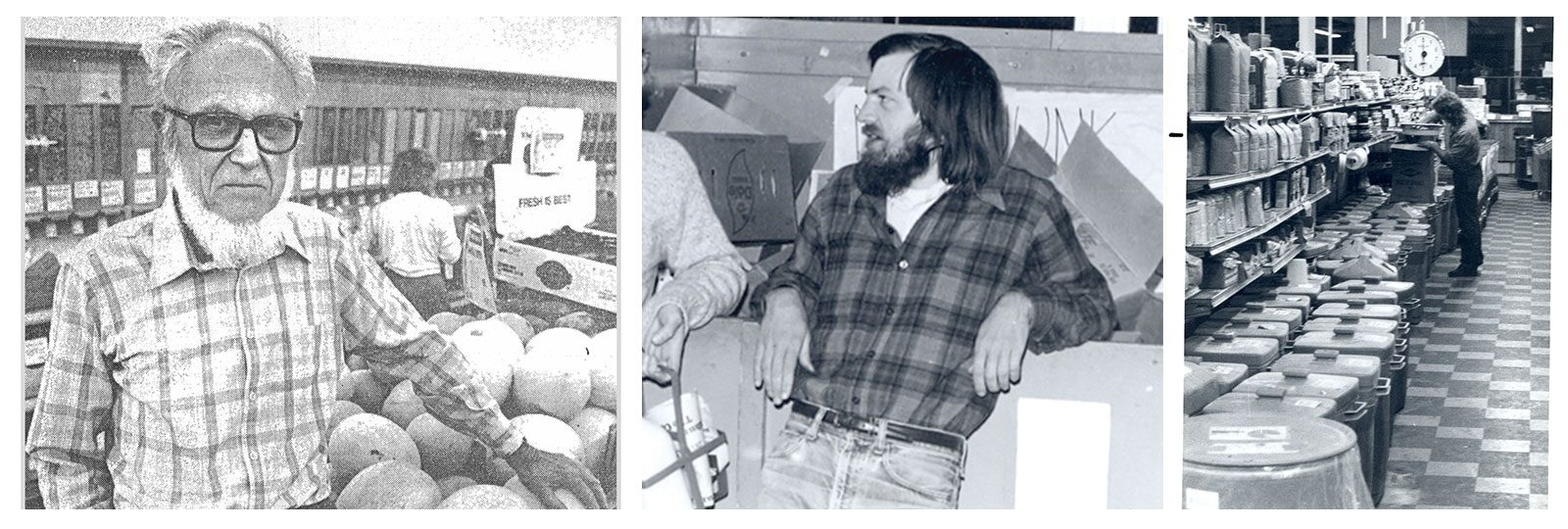

PCC’s Founding Father… and Food

This article was originally published in September 2023

A long search for the earliest recipe known to PCC comes up with a single ingredient: Idealism.

Technically, co-op founder John Affolter was known for a soybean souffle that he brought to store potlucks for decades. His daughter, Jeanne Strickland, remembers it as her mother Ruth’s dish—soaked soybeans blended with oil, flavored with herbs and baked “until

it’s done.”

But Affolter’s true legacy is an unbending commitment to his Utopian goals, and a community that shared some of his philosophy and his activism. In the process, it shaped PCC’s path. “Mr. Co-op,” as he was known, dreamed of a just society that operated by the Golden Rule, The Seattle Times wrote after his death in 1997.

“He was out to save the world. I think in some regards he was ahead of his time,” his daughter said.

In its earliest incarnation, PCC was about saving money more than saving the planet. It was informally born in 1953, when Affolter and friends formed a grocery buying club that he ran from his Seattle home.

“I’m picturing our basement with these huge bins of powdered milk and flour and stuff,” Strickland said—bulk supplies that she was paid a minimal amount as a teen to help package for distribution.

That project continued at the May Valley Co-op, a dream housing project that Affolter formed with a handful of other families in 1956. The group purchased 37 acres near Renton where they envisioned individual homes bordering an undeveloped oasis of communal open space.

PCC was formally organized Dec. 20, 1960, in the living room of that May Valley home, Affolter wrote in a personal timeline years later. (It moved to a storefront in 1967 on the health department’s insistence.) And when PCC incorporation papers were filed with Washington state on Aug. 29, 1961, its mission went beyond frugality.

The co-op’s stated purpose in those papers: “To educate its members and the interested public in 1) the wise and efficient production, purchase and use of consumers goods and services; 2) better business ethics and human relations; 3) cooperative ideals and practices—in the Puget Sound area—through employing economic techniques, and literature, bulletins, mass media, group discussion and recreation, speakers and like methods.”

Affolter himself was a lifelong activist

That forward-thinking focus fit right in with at least some of its founders.

May Valley was innovative in its social policies, author Fred Whisenhunt wrote in the journal Communal Societies in 2005. For one example, it was a rare community in that era that welcomed interracial relationships. Such couples were among PCC’s founding families; their relationships were legal in Washington state then (though not legalized nationwide by the Supreme Court until 1967), but unusual enough that Whisenhunt noted the community sometimes drew harassment. “May Valley was kind of a controversial place to live when we started going to school in the Issaquah School District,” Strickland recalled.

Eugene Robel, one of the seven people signing the incorporation papers, was a shipyard machinist and Communist Party member. Later in the 1960s he became the defendant in a significant U.S. Supreme Court case that led to the ruling that workers could not be fired from national security jobs because of such political affiliations. (Robel was supported by the American Civil Liberties Union in that case. His attorney, noted civil rights lawyer John Caughlan, later married PCC’s longtime nutrition editor, Goldie Caughlan (see “Nutrition Education from ‘Ask Goldie’ “.)

Affolter himself was a lifelong activist, as Whisenhunt wrote, so perhaps it’s not surprising many of his associates were too. A Quaker and a pacifist, he was a conscientious objector and served jail time for various causes, from climbing a fence at Bangor Air Force Base to protest Trident missiles to (at age 70) blocking the federal courthouse in Seattle to protest aid to the Contras in Nicaragua. Principled or stubborn, depending on the onlooker, he nearly lost the family home to the Internal Revenue Service by withholding taxes that represented the military’s portion of the federal budget. As Strickland said, he truly was ahead of his time: He installed a heat pump in his May Valley house, long before they were a mainstream innovation, and he co-founded a small land trust to preserve open space, decades before PCC followed suit with its Farmland Fund.

PCC is his most lasting legacy, though it was only one of his many endeavors. The May Valley co-op failed, to Affolter’s dismay, with most co-op features essentially gone by 1977. Another housing community he tried to establish, Teramanto, never thrived.

PCC was his baby, Strickland said, even though he had left active management roles as it shifted from club to store. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer paper wrote in Affolter’s obituary that he was “philosophically opposed to profits”; problematic for a grocery store that had to at least cover its expenses.

For many years he participated in the councils that each PCC store had in those days and wrote countless lengthy, reasoned letters arguing for greater member participation and decision-making. It was a myth, he wrote, that members “only want their oats and Tahini.”

He wrote in 1985 that “Being PCC’s founder and first manager I have a visceral concern for PCC.”

And if it had been his baby, he acknowledged that children grow up. “As a parent of my own adult children I respect their independence, different lifestyles and interests. I also recognize their appreciation of my devotion and longer experience. My relationship to adult PCC is similar.”