Why did Seattle’s growing zone change?

By Tara Austen Weaver, guest contributor

This article was originally published in April 2024

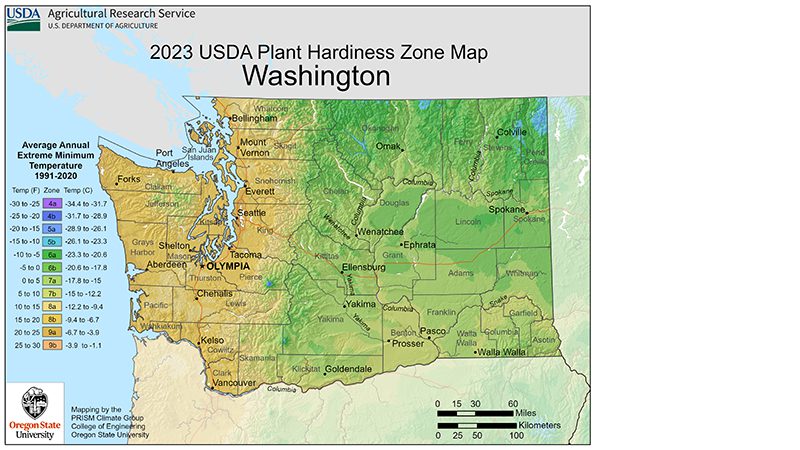

Local gardeners sensed a change in Seattle’s growing zone long before the official confirmation: our climate is getting warmer. More specifically, the city is now categorized as one plant hardiness zone warmer than before. The change recently announced by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) affects most of western Washington.

Information about growing zones is an indispensable tool for gardeners and farmers to make sure plants end up in places warm enough for them to thrive. If you’ve ever purchased a perennial plant at a nursery, the hardiness zone recommendation was likely listed on the tag. The USDA Hardiness Zone Map is the master key, breaking down the country into 26 of these zones, based on average minimum winter temperature.

Climate change: Impacts to growing zones

Since 2012, most of western Washington has been in zone 8b. This new revision moves the region into 9a—five degrees warmer. (Prior to 2012 we were zone 8a, a full ten degrees colder than we are now).

“We’ve been talking about this in our classes and presentations for a while now,” said Laura Matter, the Natural Yard Care Program Director at Tilth Alliance, a nonprofit organization dedicated to food and farming. A warmer climate has a variety of implication, not just relating to temperature. Matter pointed out that the quality of rain has changed in the Pacific Northwest—it’s harder and more intense. “The kind of torrential downpour we get now is not normal,” she says. This leads to questions about how to protect soil over the winter.

Matter is also concerned about phenology—the study of the seasonal natural life cycle—and the links a warming climate could break in these invisible but essential connections. “Are the native pollinators going to be out in time?” she said. “We can’t predict that if we don’t know what is going to happen. And bumble bees nest in the ground—what if the queen gets flooded out? We just have no notion of all the things that could happen.”

There’s a more positive flip side: the chance to grow things that are marginal for our climate. Matter speculated that warm-weather crops such as okra and sweet potato may become more common in our region. There are currently efforts underway to find cultivars most suited to our warming but still cool climate—such as the Drymifolia Collective, whose members are experimenting with growing avocados. Could the Pacific Northwest eventually become a citrus and avocado region?

According to USDA’s Agriculture Research Center, the updates “are not necessarily reflective of global climate change” because of the variable nature of minimum temperatures, more sophisticated mapping and adding data from more weather stations. But gardeners are unsurprised by the official zone change and sometimes skeptical of the caveat.

“When you’re working outside with plants every day, it’s pretty clear that things are different than they used to be,” said Hilary Dahl, who, along with husband Colin McCrate, runs Seattle Urban Farm Company, responsible for installing and maintaining hundreds of gardens throughout the greater Seattle area.

“I’m glad that they’re updating growing zones because it’s another place where people are forced to acknowledge that climate change is real and things are changing because of it.”

What vegetables to grow in Seattle

The most noticeable impacts are on heat-loving crops like tomatoes, eggplants, melons, and peppers, according to Dahl. “Ten years ago, it was very difficult for most people in the region to grow slicing tomatoes without a greenhouse,” she said. “When fall came around, all of the plants were loaded with green fruits, but few, if any, had actually ripened. Now, it’s very easy to grow slicing tomatoes outdoors. We’ve seen similar things with the other heat-loving crops, earlier and bigger harvests.” (For less common plants, try growing these unsung heroes of the Northwest garden.)

While better tomato crops might be a boon to backyard gardeners, a changing climate has an impact on commercial farmers as well—and, by extension, our food supply. The shift in precipitation patterns has led to more frequent and more serious flooding in low-lying agricultural areas—like the historic flooding along the Nooksack River in Whatcom County in 2021.

The other aspect to climate change is increasing unpredictability. In Sequim, on the Olympic Peninsula, River Run Farm is ten years into operation. “Each year is so different,” said co-founder Noah Bressler. “For example, this winter has been so warm overall, but the very cold weather just about wiped everything out for us.”

This mirrors what Jason Salvo and Siri Erickson, of Local Roots Farm, are seeing in the Snoqualmie Valley. “On average, it’s warmer in the winters,” said Salvo, “but I think the number of super cold events is going up.” This matches reports from climate scientists. Warming temperatures weakens the polar vortex that usually circles the North Pole. This pushes the polar jet stream south, bringing with it freezing temperatures that are usually contained.

Another emerging issue for farmers and gardeners is irrigation. “We used to think we didn’t have to get out irrigation equipment until June,” Salvo explained. “But now we have to start in May—and that just feels unacceptable.”

In the Seattle Urban Farm Company gardens, Dahl is also seeing increased pressure from pests and diseases. “If temperatures are warmer, more pests can overwinter,” she said, “and then the overall population builds rather quickly, which can wreak havoc on food crops. It also allows different insect pests to move into our area that the climate previously kept at bay. We’re seeing more stink bugs and flea beetles, and new species of pests every season.”

There’s potential for even greater impact. Continued warming will influence the number of “chill hours” in the state—the amount of time spent below 45 degrees F. Certain plants require a number of chill hours in order to produce a crop, and fruit and nut trees are chief among them. In a significantly warmer climate, the state’s orchard industry would eventually be impacted. Tulips, also, require a period of cold dormancy in order to flower.

Matter pointed out that these changes will cause us to adapt our garden maintenance. “We’ll have to mulch and water appropriately, and use soaker hoses,” she said. “Since we’re here now, how do we mitigate it? How do we adapt?”

Seattle writer Tara Austen Weaver is a trained master gardener and author of several books, including “Orchard House: How a Neglected Garden Taught One Family to Grow,” “Growing Berries and Fruit Trees in the Pacific Northwest,” “A Little Book of Flowers: Tulips, Peonies and Dahlias,” and “A Little Book of Hummingbirds.”