Pie-baking and the Bliss Point

By Kate Lebo, guest contributor

This article was originally published in September 2023

I began writing this essay in the gap between Spokane’s rhubarb and strawberry season, which hit this year in early June. For one more week, the only strawberries at our farmers markets still come from California, though the farm’s sign would like us to believe they’re from Wapato. They can’t fool me.

I know the taste of an out-of-state strawberry—sour in a shallow way that’s worth forgiving only in this specific gap between the rhubarb harvest and the moment when, after a six-month pause, the rest of our local fruit season begins. This is when I get impatient, buy the “Wapato” strawberries, and forgive.

My 2-year-old doesn’t think twice about any of this. When he sees a strawberry of any provenance he says “strawberry” and wants it. He seems to enjoy a sour, white-cored, Well Pict giant the same as a sweet red Albion from Umatilla County.

These days all he will eat is fruit and crackers and pickles and hummus, but mostly fruit. He loved fruit pie as soon as he could chew. Recently he’s begun to ask for it by name, which still startles me—this moment when I’ve realized he knows the word for something that’s a totem of our family’s life, and I hear that word as a clear command from his little mouth. “Pie!” he says, when I’m trying to feed him squash. “Pie!” he says, then throws his chicken parm on the floor.

By this point in the season I’ve made four pies from rhubarb I planted two years ago, during Cy’s first summer. I’d planted a different rhubarb eight years ago, the first year we lived in this house, and it bolted almost immediately (as if it wanted to run away!), raising a flower that looked sometimes like lace and sometimes like confetti while its sour stalks grew tough. I gave that first rhubarb years to get its act together, but it never did. Now I think the fault was mine. I planted it in a spot so hot, even tomatoes drop their blossoms there. It took me many seasons to understand this. For a couple years I told myself the rhubarb was decorative, it was fine that we couldn’t eat it, the flower was so strange and awesome, the way it appeared like a cloud and then slowly, over the course of several weeks, extended itself over the plant like a tattered periscope. But during the pandemic, I got serious about feeding the family from our yard again. The old rhubarb patch became a sage and thyme bed, and the new rhubarb lives near our west fence where it gets a break from Eastern Washington’s summer sun every day. In return, it supplies us with sour stalks until well after strawberry season is over.

This year, in mid-May, the new rhubarb stalks had a melon-sweetness to them, which was confusing but delicious. By early June, the same amount of sugar—1/4 cup per cup of rhubarb, my standard—made a pie so tart, the sourness felt like heat on my tongue. Even as I said this out loud to my dinner companions, I wasn’t sure if this could be true. I might have been disassociating a little, stepping away from the pain of sourness (mentally, I mean; I was seated for this entire experience) so I could maintain my composure. At this remove, the flavor lost what made it a flavor and became instead a kind of heat.

If the fruit doesn’t have that depth, I tell my students to adjust ingredients until it does. Usually that doesn’t mean more sugar. Usually that means another pinch of salt and another squeeze of lemon.

I’ve never loved Sour Patch Kids or hot lemon water or sweet and sour pork. Sourness, even more than bitterness, feels like an injury I’m doing to myself, one that twangs my nerves like fingernails on a chalkboard. I can actually feel those nerves panicking—they emit a dull ache close to my lymph nodes. Sometimes when this happens I put my fingers to them, like I’m checking to see if I am sick.

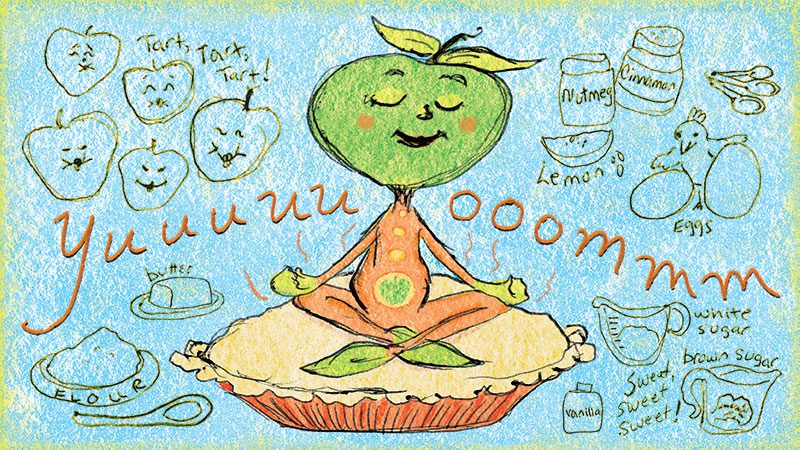

But without sourness, fruit pie isn’t very interesting. When I teach the cooking class I call Pie School, there’s this moment when I tell my students to taste the fruit/sugar/lemon/salt/spice mixtures in their bowls. “This pie filling is going to taste good,” I say, “it’s fruit and sugar. But it should taste a little more than that. Like something you don’t want to stop eating.” It’s hard to describe what I’m after in print, but easy in person with a bowl of what will soon be fruit pie. We take a bite and decide, from how it tastes, whether or not we’ve hit the spot. That extra depth of flavor can feel like a craving has been quenched and kindled at the same time. If the fruit doesn’t have that depth, I tell my students to adjust ingredients until it does.

Usually that doesn’t mean more sugar. Usually that means another pinch of salt and another squeeze of lemon. The sweet spot—what is not just a sweet spot, and in fact is also called a “bliss point,” where a flavor’s elements are calibrated to induce both satisfaction and craving—is what we’re going for. The term was coined by Howard Moskowitz, a market researcher and psychophysicist working for the processed food industry, to describe when foods have been “formulated to produce a state of satiety, pleasure and hedonia in those who consumed them,” according to a paper published by npj Science of Food. I’ve used that bliss point as a metaphor in other essays but during Pie School I mean it literally, as threshold we can physically find.

From an evolutionary perspective, it’s not clear why humans can sense sour tastes at all. Sweet is a pretty reliable indicator of calories, as is umami. Bitterness can signal poisons to avoid, and salt is necessary for our bodies to function. But sourness? It tends to indicate that food is acidic, which might mean it has Vitamin C, but might not. Sometimes it means that the fruit is unripe, but not always. Some research indicates that babies like sourness. Maybe that explains Cy’s taste for white strawberries and dill pickles.

For piemakers, sourness is an indicator that this fruit will probably perform well when baked. Strawberries, if you ask me, are useless in pie. So are sweet cherries. What complexity they have is overwhelmed as they break down in the oven. Raspberries, apricots, gooseberries, quince—those are pie fruits. Rhubarb, as you may know, is even called “pie plant,” though that may have more to do with its early profusion of stalks than their sourness.

When I was experimenting with local berries for the “Difficult Fruits” chapter of the reissue of my cookbook “Pie School”, most of the fruit had flavors that were less immediately appealing than traditional pie fruits, which makes me wonder if the bliss point is something we breed into domesticated fruit. Elderberries are astringent and not very sweet on their own. Sarvisberries are sweet and almondy, without much acid. Huckleberries are the easiest fruit here, taste-wise (not gathering-wise), but their sour-to-sweetness varies with location, species, and the amount of water and sunlight they soaked up over the summer. These fruits are difficult because they’re less familiar to many of us and harder to obtain, but also because their assertiveness or astringency or sheer variability require a little more finessing to reach what most of us would consider a bliss point. Most of us can’t just follow a recipe to make a delicious sarvisberry pie. We must also taste the filling and adjust its flavor to meet the bliss point. That’s true with all fruit pies, but especially true for fruits found outside the aisles of the grocery store.

By the time you read this, it will be apple season, the easiest and possibly most rewarding pie fruit. You can find great pie apples at local grocery stores about as easily as you can find them at local orchards, or even in your neighbor’s backyard. As you select fruit to bake, just remember that the best pie apples might feel like a little war in your mouth when you eat them raw. If it’s easy to eat out of hand, save the apple for your lunch sack. If, when you take a bite, the fruit makes you flinch, it’s probably a pie apple. While you suffer through your bite, remember that sweet and sour are not in opposition. They need each other. Without acid, sweetness is insipid. Without sweetness, sourness tastes gross, even painful. You can read all sorts of life lessons into that. Or you can just make a pie.

Plum Thyme Pie

This open-face pie (it works wonderfully as a galette too) was inspired by a small batch of plum-thyme jam, the sleeper hit of a canning marathon that also included plum ginger, plum bourbon and plum vanilla. Thyme pushes Italian plums toward their savory side.

Makes 1 pie

½ recipe any double-crust pie dough (for a single crust)

5 cups (about 25 to 30 small) Italian prune plums, halved lengthwise and pitted

½ cup honey

Juice of ½ medium lemon (about 1½ tablespoons)

1 teaspoon finely chopped fresh thyme leaves

2 tablespoons unsalted butter, melted

Pinch of salt

5 tablespoons flour

Make the dough. Roll out the bottom crust and place it in a 9- to 9½-inch plate. Tuck the crust into the plate, trim the edges, and fold them into a ridge. Refrigerate the crust while you prepare the next steps of the recipe.

Preheat the oven to 425 degrees F.

In a large bowl combine the plums with the honey, lemon juice, thyme, butter, and salt. Taste and adjust the flavors as needed. Gently stir in the flour and set the filling aside.

Retrieve the bottom crust from the refrigerator. Arrange the plums inside the dough in snug concentric circles, starting at the edge and working your way in. Pour the remaining liquid, if there is any, over the top.

Bake the pie in the middle of the oven for 10 to 15 minutes, until the crust is blistered and blond. Reduce the heat to 350 degrees F and bake for 40 to 50 minutes more, until the crust is brown and the juices bubble slow and thick at the pie’s edge.

Cool on a wire rack for at least an hour. Serve warm or at room temperature, cut into wedges and accompanied by slightly sweetened whipped crème fraîche. Store leftovers on the kitchen counter loosely wrapped in a towel for up to 3 days.

Note: This pie’s success showed me that what works in jam will very likely work in pie. Which means your experiments in ginger, bourbon or vanilla are likely to yield hits as well.

All-Butter Piecrust

Makes 1 double crust

In pursuit of “perfect” piecrust, some recipes advocate for this secret ingredient or that. Vinegar, maybe (which slows down gluten formation), an egg (which adds protein to the dough, binding it together and making it easier to roll), or even vodka (which evaporates during baking without having developed wheat flour’s gluten). These additives are especially useful when you’re making piecrust in a food processor, which can work the hell out of the crust with one pulse too many.

But they aren’t necessary. Not when you’re making dough by hand. With my method, this all-butter crust recipe creates a dough that’s as tender as it is flaky, which means it’s not going to explode into shards like a puff pastry when you take a bite. Rather, it will frame the filling in rich, light pastry layers that are strong enough for you to pick up a slice and eat it by hand.

This crust is so easy to work with, its ingredients so easy to find and store, I use it in all my pie classes. When making pie for myself, it’s the recipe I lean on like an old friend.

2½ cups flour

1 tablespoon sugar

1 teaspoon salt

1 cup (2 sticks) well-chilled unsalted butter

Fill a spouted liquid measuring cup with about 1½ cups of water, plop in some ice cubes, and place it in the freezer while you prepare the next steps of the recipe. The idea is to have more water than you need for the recipe (which will probably use ½ cup or less) at a very cold temperature, not to actually freeze the water or use all 1½ cups in the dough.

In a large bowl, mix the flour, sugar and salt. Cut ½- to 1-tablespoon pieces of butter and drop them into the flour. Toss the fat with the flour to evenly distribute it.

Position your hands palms up, fingers loosely curled. Scoop up flour and fat and rub it between your thumb and fingers, letting it fall back into the bowl after rubbing. Do this, reaching into the bottom and around the sides to incorporate all the flour into the fat, until the mixture is slightly yellow, slightly damp. It should be chunky—mostly pea-size with some almond- and cherry-size pieces. The smaller bits should resemble coarse cornmeal.

Take the water out of the freezer. Pour it in a steady thin stream around the bowl for about 5 seconds. Toss to distribute the moisture. You’ll probably need to pour a little more water on and toss again. As you toss and the dough gets close to perfection, it will become a bit shaggy and slightly tacky to the touch. Press a small bit of the mixture together and toss it gently in the air. If it breaks apart when you catch it, add more water, toss to distribute the moisture, and test again. If the dough ball keeps its shape, it’s done. (When all is said and done, you’ll have added about ⅓ to ½ cup water.)

With firm, brief pressure, gather the dough in 2 roughly equal balls (if one is larger, use that for the bottom crust). Quickly form the dough into thick disks using your palms and thumbs. Wrap the disks individually in plastic wrap. Refrigerate for an hour to 3 days before rolling.

Make pie with Kate Lebo

Kate Lebo, author of “Pie School,” will teach PCC cooking classes Oct. 21 at PCC’s Green Lake store and Bellevue store.

Sign up!Easy as pie

Interested in flexing your pie-baking muscles after learning from Kate Lebo’s Pie School? Many PCC pie recipes are available online. Highlights include:

- Fall is a great time to try PCC’s most popular recipe, the Old-Fashioned Brown Sugar and Cinnamon Apple Pie created by former executive chef Lynne Vea. Get the recipe and hear how it was created here.

- Ready to start thinking about pumpkin pie? If you want to go beyond the recipe on the back of the canned pumpkin container, PCC’s version uses a roasted sugar pie pumpkin, milk and cream. Find it here.

- Want a smaller-scale project? Use packaged frozen puff pastry dough to make hand-held fruit pies. See this apple version here.

- Try a galette, a more forgiving and flexible form of pie where the crust dough is folded around the filling. Galettes can be sweet, like the fresh fruit version here, or savory, like the winter squash, apple and blue cheese galette.