Black farmers, Bittman and the way forward

This article was originally published in January 2022

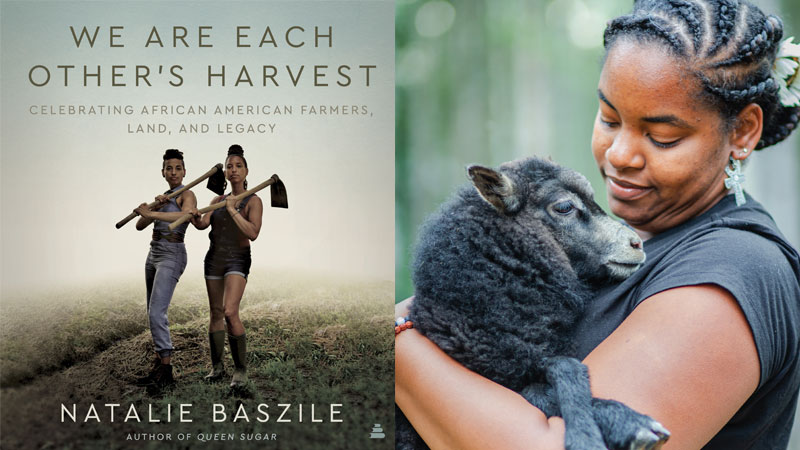

Mark Bittman, one of the country’s most influential food writers, hosts a podcast titled “Food Matters.” He recently spoke with local farmer and Sound Consumer contributor Melony Edwards in a segment titled “Black Farmers and the Way Forward.” Edwards appeared with author and filmmaker Natalie Baszile to mark Baszile’s book, “We Are Each Other’s Harvest: Celebrating African American Farmers, Land, and Legacy,” which included Edwards.

While farming is often presented simply as a grueling, challenging job—or, for Black farmers, as a profession to be avoided because of slavery’s legacy—Baszile’s book showed joys along with challenges, and a rich expanse of possibilities.

An edited, condensed excerpt from their conversation follows; the full podcast is available here.

Bittman: Melony, you spent five months learning about farming at Calypso Farm in Fairbanks (Alaska). Was that a joyful experience, and what did you do when you were there?

Edwards: Yes, that was an amazing, joyful experience. My time at Calypso Farm actually came after I had been farming for about three years and doing large production vegetable growing and direct sales to chefs around the Seattle area. In that time, I learned I have valuable experience in how to grow vegetables and produce vegetables. But as a farmer, there are many skills that you need, like “How do you fix a tractor?” and “How do you build a small shed?” Calypso Farm was me taking a step back and saying, “I’m going to go to farm school, and I’m going to take the time to learn the skills that farmers need.” Also, as a Black woman, I was seeing there were a lot of skills that you don’t see a lot of Black people involved in, like blacksmithing, and at that time I didn’t see a lot of Black people in the world of fiber and textile art…So I learned things like small engine repair… Natalie helped build a log cabin while she was there, and we were also working with natural fibers and textiles. So they raised sheep, we sheared them, we washed the wool, spun the wool into yarn and dyed it.

Bittman: I’m curious where you are on your journey.

Edwards: I am working for a nonprofit organization that focuses on organic seeds, and one of the many goals is to foster a community of farmers stewarding open-pollinated seeds in addition to advocating for policy reform on national organic platforms. I also serve as a board member for the National Young Farmers Coalition, a national advocacy network of young farmers fighting for the future of agriculture. This is really important to me because almost two thirds of U.S. farmland is now managed by someone over 55, and farmers over 65 outnumber farmers under 35, and in the next decade 400 million acres of U.S. farmland will change hands from the current generation of retiring farmers. So we really need to have a younger generation of farmers that are prepared to be stewards of the land and have the tools and resources to be successful in doing so. I am also cultivating my own farm enterprise that focuses on growing natural dye flowers such as indigo and marigolds (and) fibers for textiles…and I am on my own seed journey of learning how to be a seed steward. I have a particular interest in culturally significant seeds among the African diaspora and want to adapt them to thrive in the Pacific Northwest climate…And I’m hopeful that the right opportunity to purchase land will come so I can fully realize my dream of farming.

Bittman: We want there to be more farmers in general, more young farmers in general, more young farmers of color and women in particular, but then we want people to be farming in a different way at the same time. I’ve talked to a lot of farmers (that) have the privilege of having land that many of them inherited, and therefore (are not dealing with) being in debt, but at the same time they feel that there’s no official support to do farming differently or better. They’re like “Yeah, we don’t really care whether we grow corn and soybeans or fruits and vegetables, but we’re being paid to grow corn and soybeans and we really don’t have a choice.”

Edwards: I like to meet people where they are, and just also point out that even commodity farmers care about the product that they’re producing, the soil, the land and sometimes the animals that they’re caretaking for. So I think that is one thing that we should recognize and value—and then, meeting them where they are, provide them with the tools and resources so that they can make and implement changes. Oftentimes it can be very costly, especially when we’re talking about the hundreds of acres that some people, particularly commodity crops, occupy. They often get government subsidies to continue in the practices that they’re doing, so they’re already incentivized to continue with the practices that they’re doing. So what we really need are incentives for people to transition to sustainable regenerative and organic practices. We don’t really have a system for that at this moment, outside of saying, “Oh, it’s gonna make the soil better, and it’s going to maybe give you more yields.”

Bittman: I wonder if either or both of you have a vision of how land might be redistributed more favorably. I think before Ta-Nehisi Coates’ (2014 Atlantic article) about reparations, it was a small select group of people that were talking about reparations, and then it became a common topic to the point where it even gets talked about in Congress…And now I think the (common) phrase is land reform. How do we get land into the hands of people…who were mostly shut out of the great land giveaways of the 19th century?

Baszile: It’s tricky, (though) it should be simple. At some point the (federal) Justice for Black Farmers Act talked about allotting farmland that the U.S. government currently owns and setting that land aside for young farmers. I think there is an opportunity for a different kind of impact investment. This is just an example, I was talking with some folks, Black people who have done well financially, whether they’ve been in investment banking, or tech, who have expressed interest in coming together and buying land and then turning that land over to young BIPOC farmers who want to farm, with a different set of expectations about the return. They would not be looking to profit, they would be looking to put that land in the hands of young people who want to farm. I think it’s going to be a combined effort…Government is a slow-moving ship, you know, and there are all kinds of obstacles. I think that there are probably opportunities in the private sector for people to come together. I think there’s also an opportunity for current landowners. There’s a lot of land out there that’s not being (farmed), and I think that there are opportunities for those people to come to the table and offer that land in partnership with young farmers or nonprofits and give people an opportunity to put into practice all of the things that they have learned. I think we’re going to have to think creatively, in other words, in order to really tackle this.

Edwards: Some of the programs that we do have out there for land transition are called farmer to farmer programs, where farmers have a direct link with the next generation and are offering more cost efficient land transfers to incoming farmers. Land is so expensive right now, though, a lot of us can’t afford it. One of the things that really hurts young farmers entering the market is also student loan debt. There’s a lot of work that needs to happen within policy and reform to really help the next generation of farmers access land.

When I think about land models, we have a lot of younger farmers that maybe don’t have the financial resources to pay for land, forming cooperative farm models. I think that’s one of the many ways we’re going to see this land reform happen over the next generation. And then as far as reparations, the term reparations often is thought of as 40 acres and a mule, but I feel like what we should be asking for is 40 acres and a tractor. Because if we were to stay up with the times, and technology and modernization, in order to steward 40 acres you need a tractor. I just think that we just need to be a little bit more realistic in our ask of what a reparation or land reform looks for. And then I’ll just say one last thing. I’ve been offered free land a few times, and generally it comes with land that’s been farmed conventionally for years, has a lot of toxins in the soil, and it doesn’t have any water capacities… Not to be like “I’m being choosy,” but I think that realistically, if you get a piece of land that doesn’t have access to water, how are you going to water your animals? How are you going to water your crops? You know, how are you going to live off of that land? I think that we need to really have land that is sustainable.

Bittman: It doesn’t sound at all like you’re just being choosy, it sounds like you’re saying we want more than crumbs off the tables, which is exactly right. What’s the honorable relationship between land and people? And do we see that, can we hope to see that?

Baszile: Part of what was so exciting to me in working on this book was to witness the shift that I think is happening, where people’s conversations about land, people’s understanding of their connection to the land, is really changing. Part of the silver lining of this last 18 months with COVID is people have been forced to really ask themselves some questions about where their food comes from…So when I look ahead to the future what I see is a level of activism and engagement, a sense of community that people have around food sovereignty and food security that I’ve not seen before. And that gives me hope.