Saving farmland, supporting farmworkers?

By Tara Austen Weaver, guest contributor

This article was originally published in July 2021

Agricultural land trusts are in the business of preserving land, not building on it.

And yet, the farmland that the trusts often save from development doesn’t exist in isolation. Many farmworkers earn low wages and live in crowded and substandard conditions. Farmers, who are trying to keep production costs low, are not often willing to incur the additional expense of subsidizing housing. This past year, COVID-19 highlighted the vulnerabilities of a system where adequate space and sanitation cannot be guaranteed.

Some creative thinkers are wondering if the same solution that saves the land can also support the workers. Could affordable housing for farmworkers be part of a responsible approach to preserving land?

Goals and complications

On the Olympic Peninsula, the Jefferson Land Trust (JLT) recently took on this challenge. While protecting 16 acres of valuable farmland in the Chimacum Valley and restoring salmon habitat along a portion of Chimicum Creek, they hoped to partner with another organization to build housing for farmworkers on a portion of the land that ran along a road. As JLT executive director Richard Tucker explains, affordable housing is hard to come by in the area.

“Farmworkers shouldn’t have to commute,” he said. “They should be able to live in the community, especially if they have a family.”

He took some inspiration from a 2016 collaboration of land trusts in North Carolina. As part of a plan to protect 900 acres of open space, Conserving Carolina decided to sell a small parcel that ran along a road and had been logged. Instead of selling to the highest bidder, they arranged for the land to be purchased at below-market rates by a nonprofit organization that develops affordable housing. While the housing that was built was not farmworker specific, it’s the sort of creative collaboration that can provide yields: in this case, 32 single-family homes in an area that needed them. Turner wondered if a similar solution could serve Jefferson County.

The answer turned out to be complicated. Because land trusts are not established to build or maintain housing, any development project requires the right partners (generally community housing advocates) and adequate funding. Even if those two requirements can be met, other issues can prove problematic, especially for rural housing projects.

While the Chimicum property would be able to tap into a county water line, the rural area has no sewer system and building a septic system for multifamily housing would have been expensive. Additionally, zoning regulations set in place to limit development in the area allow for only one dwelling unit per 5 acres of land; any multiunit building would require a change or exemption from the code.

“Conceptually, there should be a way to find a solution,” says Tucker,” but there are significant challenges. Tucker says that the county commission is still looking into finding solutions. But for the meantime, plans for Chimicum Commons, as the project was to be named, are on the shelf.

Civil Rights roots

Other models offer promising avenues to explore. In 1969 the first Community Land Trust (CLT) was established in Albany, Georgia, drawing inspiration from the British Garden City movement, India’s Gramdan Villages, and the Moshavin in Israel—all communities where land is held in public trust while housing can be rented or purchased privately.

The Georgia land trust project, called New Communities, grew out of the Civil Rights movement and concern that, due to discrimination, Black farmers were not being able to access farmland. Established on 5,735 acres, New Communities was the largest Black-owned parcel of land in the country, with greenhouses, a farmers market, sugarcane mill, a printing press, and plans for schools, health facilities, industrial and recreation areas. In 1985, however, drought hit the area. While neighboring white farmers were given U.S. Department of Agriculture emergency loans to cover the additional irrigation costs, the loan application from New Communities was denied. A subsequent landmark 10-year lawsuit known as Pigford v. Glickman was decided in favor of New Communities, but by then the land had been foreclosed on and sold to white farmers for a fraction of its value.

The idea of a CLT, however, had taken root. One of the founders of New Communities—Robert Swann, co-author of “The Community Land Trust: A Guide to the New Model for Land Tenure in America”—relocated to Massachusetts, where he was involved in establishing the Community Land Trust of the Southern Berkshires, whose holdings include both residential developments and a working farm.

While CLTs do sometimes encompass community gardens or farmland, their focus is on affordable housing. One CLT in Vermont—championed by Senator Bernie Sanders while he was mayor of Burlington—now houses 2,000 members in apartments and homes owned or rented by occupants. Because the units are on land owned by the trust, costs can be kept lower, while still allowing purchasers to build equity. Community land trusts have sprouted up across the country—including here in Washington, where such properties can be found from the city of Seattle to rural islands in the San Juans, and many places between.

A fusion solution?

Could some fusion of agricultural land trusts and housing-focused community trusts be the solution to farmworker housing? Could the concept be used to expand access to farming for disenfranchised communities? It remains to be seen. “Affordable housing for farmworkers is definitely a topic of conversation within the Washington land trust community,” says Molly Goren, communications director of Washington Farmland Trust. Though no projects are yet in the pipeline, numerous stakeholders are trying to build a land conservation model that includes accommodating workers. “We’d be thrilled to see a project that meets multiple community needs come to fruition,” Goren says.

Some existing projects provide inspiration and ideas to navigate the complex issue. In 2016 the Yakima Housing Authority completed a farmworker housing project in Toppenish in the Yakima Valley. The 30-unit project was designed by José Bazan, a Bellevue-based architect who grew up in the area, a son and grandson of farmworkers who had come north from Texas. Bazan remembers waking up at 4 a.m. to pick asparagus before school, then returning to the fields to help his parents after his classes were over. He considers lack of affordable housing a public health crisis—even in non-pandemic times—as low-wage farmers often have to choose between paying for food and housing or going to the doctor. This project was an opportunity to address the challenges facing his community and to give back at the same time.

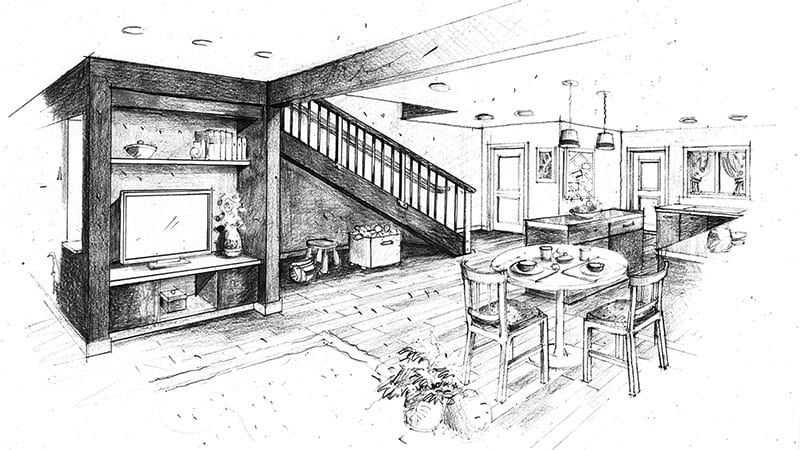

The project, which relied on a mix of public and private funding, was designed to be as culturally specific as possible. “The thing about farmers is that it’s not just one person,” Bazan explains,” it’s generations—grandparents, parents, children; it’s a community culture.” Because of this, play areas were incorporated into the design, and each unit was arranged with a kitchen or living room window overlooking the play area for supervision. A third bedroom was placed on the ground floor, to accommodate any grandparent accessibility needs and provide extra privacy. When the painter on the project complained that the bright exterior colors made him change out his equipment too frequently, Bazan told him, “Our people are colorful.”

The Toppenish project encountered similar challenges to most any farmworker housing project, namely utilities. “It’s a problem,” Bazan agrees. “It does get to be expensive—and it depends on the soil. It could be good topsoil for farming, but not for building. And water, electricity, septic, zoning—the city council has to get everyone to agree…it can take years,” he says.

“A lot of people shy away from such complicated and long-term projects,” Bazan explains. “They say, ‘I can’t be working on this for three years!’”

A forever goal

That’s where other nonprofit partners, like the land trusts, could come into play. Land conservation is a long-term endeavor, with the goal being forever.

On the coast south of San Francisco, Peninsula Open Space Trust (POST) is putting this idea to work. With help from funds raised by a half-cent sales tax increase approved by San Mateo County voters in 2016, the trust renovated an older farmhouse and installed four new three-bedroom homes for use by agriculture workers on farms leased from POST. This is part of an initiative trying to address the loss of farmland along the San Mateo coast (35% of agricultural land in the area has been lost since 1980). “Farms need more than just land to survive,” explains Laura O’Leary, senior farmland project manager for POST. A reliable workforce is also necessary.

For Bazan, the architect, providing farmworker housing is a moral imperative. “We can’t be taking advantage of the people who put food on our table,” he says. “When we put a salad on our table we don’t think about how those carrots had to be grown and harvested by someone, but we should.”

Seattle writer Tara Austen Weaver is author of three books: “The Butcher and the Vegetarian,” “Orchard House: How a Neglected Garden Taught One Family to Grow,” and “Growing Berries and Fruit Trees in the Pacific Northwest.”