The Heirloom Collard Project is a surprisingly Northwest success

By Melony Edwards, guest contributor

This article was originally published in May 2021

In 1912 poet James T. Cotton Noe described collards as such, “But I have never tasted meat, nor cabbage, nor corn, nor beans, nor fluid food on half as sweet as that first mess of greens.”

As an African American farmer in the Pacific Northwest (PNW), with family roots from the South, my enthusiasm for these broad-leaved greens matches that of Noe’s. This year I grew out 20 different varieties as one of eight full participant trial sites in The Heirloom Collard Project. It’s a national cooperative endeavor with the goal of regenerating seed stewardship and food traditions around rare and almost forgotten varieties of collards.

I savored every bite and hope you’ll join me in making 2021 the year of the collard.

To my mind, this globally influential crop is impacting the world, one bunch at a time. Collards, while popular among Africans and generally assumed to originate in Africa, are actually from Eurasia, as food historian Michael Twitty discussed during a virtual Collard Week hosted by The Heirloom Collard Project and Culinary Breeding Network. As speakers discussed, they were later popularized by African Americans in Southern cuisine. Collards hold connections to African American slavery, as they were one of the only greens that slaves were able to freely grow and consume. They were a staple food that sustained our ancestors’ dietary needs. Later, as enslaved people gained their freedom, they became a symbol of our identity and resilience. Their resonance is deep and wide; collards are steeped in cultural influences as far-reaching as Greek, Roman, Portuguese, Brazilian and the Kashmiri region of India.

While the Southern states have stewarded collards for generations, the crop is capable of thriving in the Northwest as well. It’s a member of the brassica family, after all, the same species as our ubiquitous kale. Now, thanks to The Heirloom Collard Project, local gardeners and growers can sample an unprecedented range of varieties of collards while helping preserve the diversity of this species long-term.

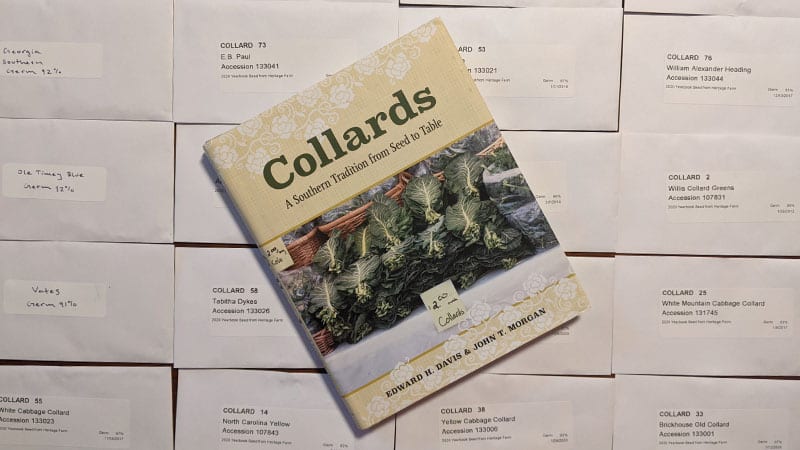

The roots of this project were planted when, to prevent collards being merely classified as a weed, Edward H. Davis and John T. Morgan embarked on a rescue mission to preserve the cultural significance of this undervalued culinary masterpiece. In their 2015 book, “Collards: A Southern Tradition from Seed to Table,” they detailed over 60 curated varieties, memorializing them, their seeds, their stories and the seed stewards. As other leafy greens become more popular and seed companies cultivate fewer diverse options, many varieties of crops would die out without champions like these to preserve them. Now classified as rare heirlooms, some collard varieties must be shared and consumed through other avenues to fortify and amplify their existence.

Seed steward Ira Wallace of Southern Exposure Seed Exchange, a cooperatively owned seed company specializing in heirloom and open-pollinated seeds, spearheaded the idea of reviving the collard legacy. In 2016 she requested 60 rare heirloom varieties from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) seed bank (grown by geneticist Mark Farnham, who was on the trip with Davis and Morgan, according to Mother Earth Gardener magazine). Wallace wanted to test trials of the seeds at the nonprofit Seed Savers Exchange Heritage Farm in Decorah, Iowa. Still forwarding the momentum, The Heirloom Collard Project followed, born out of Davis’ and Morgan’s dedication—a cooperative endeavor including Southern Exposure Seed Exchange; Seed Savers Exchange; Working Food, a Florida-based nonprofit dedicated to local food resiliency; and The Utopian Seed Project, a North Carolina-based nonprofit supporting diversity in food and farming. Its goal is regenerating seed stewardship and food traditions.

The Heirloom Collard Project reached out to farmers and gardeners across the nation seeking participants willing to host a collard trial, and that call was well received by collard fans in the Pacific Northwest. This year, four PNW trial stewards participated in The Heirloom Collard Project coordinated via SeedLinked, a digital platform. Each participant grew out 20 different varieties, with eight full trial sites nationally, as well as 200 other participants who grew out at least three varieties across the nation. PNW trial sites were hosted by the Washington-based Organic Seed Alliance and Ebony By Nature (my farm), and the Oregon-based Mudbone Grown farm (owned by another Black Farmer) and North Willamette Research and Extension Center Learning Farm.

It may seem surprising that so many trial sites are based in the Northwest for a crop that is commonly associated with the South, but our region is a good fit for these trials for many reasons, and home to bumper crops of other Brassicas.

We already know that these collard varieties perform well in the southern United States, as those locations have stewarded collards for generations. However, there is great value in trialing in the PNW to learn which of these varieties will thrive in our cooler climate. The mild winters of the PNW make the region ideal for trials because collards are a cool season crop that can be harvested well into early winter and are more frost resistant than any other cabbage variety. Also, much like Brussels sprouts, collards only get sweeter after a kiss from frost.

This hearty vegetable carries a lofty legacy in addition to its nutritional value (it’s high in vitamin A, C and calcium, among others), and grows almost effortlessly in the seemingly barren wintered grounds. Collards, aka the “headless cabbage,” is one of the oldest members of the Brassica family, which also includes kohlrabi, broccoli and the kale mentioned earlier, among others. Chef and food historian Twitty notes that Green Glaze is one of the oldest varieties we know of dating back to the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and Georgia Southern dates back to the 1860s-1880s. Collard varieties have a range of flavor profiles including sweet to earthy to nutty to almost peppery. Full of fiber and antioxidants with the choice to eat them raw or cooked, over 70 different varieties of collard greens exist ranging in deep shades of green, to light yellow-green, glossy and even purple!

To grow your own collards, or even save seeds, from the trialed varieties, I highly recommend ordering from the online shops of Uprising Seeds (US), Southern Exposure Seed Exchange (SESE), or Seed Savers Exchange (SSE). It has been a collective effort to share the trial results however, not all varieties are readily available to purchase due to limited seed stock. I encourage you to share any excess seed with fellow collard enthusiasts who may encounter limited availability.

Here are several varieties I recommend, many from The Heirloom Collard Project trials (and seed companies from which to source them): Champion (US) & (SESE)—Although not part of the trial, it is a consistent performer and most often found in grocery stores across the PNW; Cascade/Green Glaze (US) & (SESE); Georgia Southern (SSE); Jernigan Yellow Cabbage (SSE); Ole Tiemy Blue (SSE); Vates (SSE) & (SESE); Yellow Cabbage (SESE); White Mountain (SESE)—Unfortunately White Mountain did not perform as well as others in the PNW climate, but more “trials” would be beneficial.

The continued vision of The Heirloom Collard Project is to generate enthusiasm around growing and eating collards as well as to embrace the cultural heritage of the culinary traditions that sustained descendants of Africa for decades. You are invited to celebrate history and amplify the seed stewards who cultivated and preserved these unique varieties for future generations. Without their dedicated work we would not be able to share these varieties and the stories they carry forth with you today. It is our goal to pass the torch to new seed stewards who will foster their overall preservation.

I hope you are inspired to grow and share the love of collards, together. As I said earlier let us make 2021 the year of the collard! As Southern barbecue master and heirloom collard grower Lathman “Bum” Dennis would say, “They’re not a side dish. They’re what I would call a feature.”

On Melony Edwards’ journey of reclaiming farming she landed on a 20-acre mixed vegetable farm in rural Western Washington, where she immersed herself in small-scale agricultural practices. Currently, she is embarking on her own farming business, Ebony by Nature, which focuses on natural dye plants, fiber arts and seed growing.