Biochar and carbon: Crop resiliency in a changing climate

by Kai Hoffman-Krull

This article was originally published in February 2019

One of the newest methods for increasing crop resiliency in a changing climate is an historic practice in Pacific Northwest agriculture. It involves incorporating charcoal in the soil.

If you had walked the coastline of the San Juan Islands in the years before European settlers arrived, you would have seen planted fields defined by rows of stones shaped in circles along the contour of the land. Within these stones were plants that looked like grasses with clumps of purple petals spreading along vertical green edges. These flowers are called Camas, cultivated for their tubers similar to a potato and eaten by the Coast Salish. If you had reached into the soil of these fields you would have found it to be the color of charcoal.

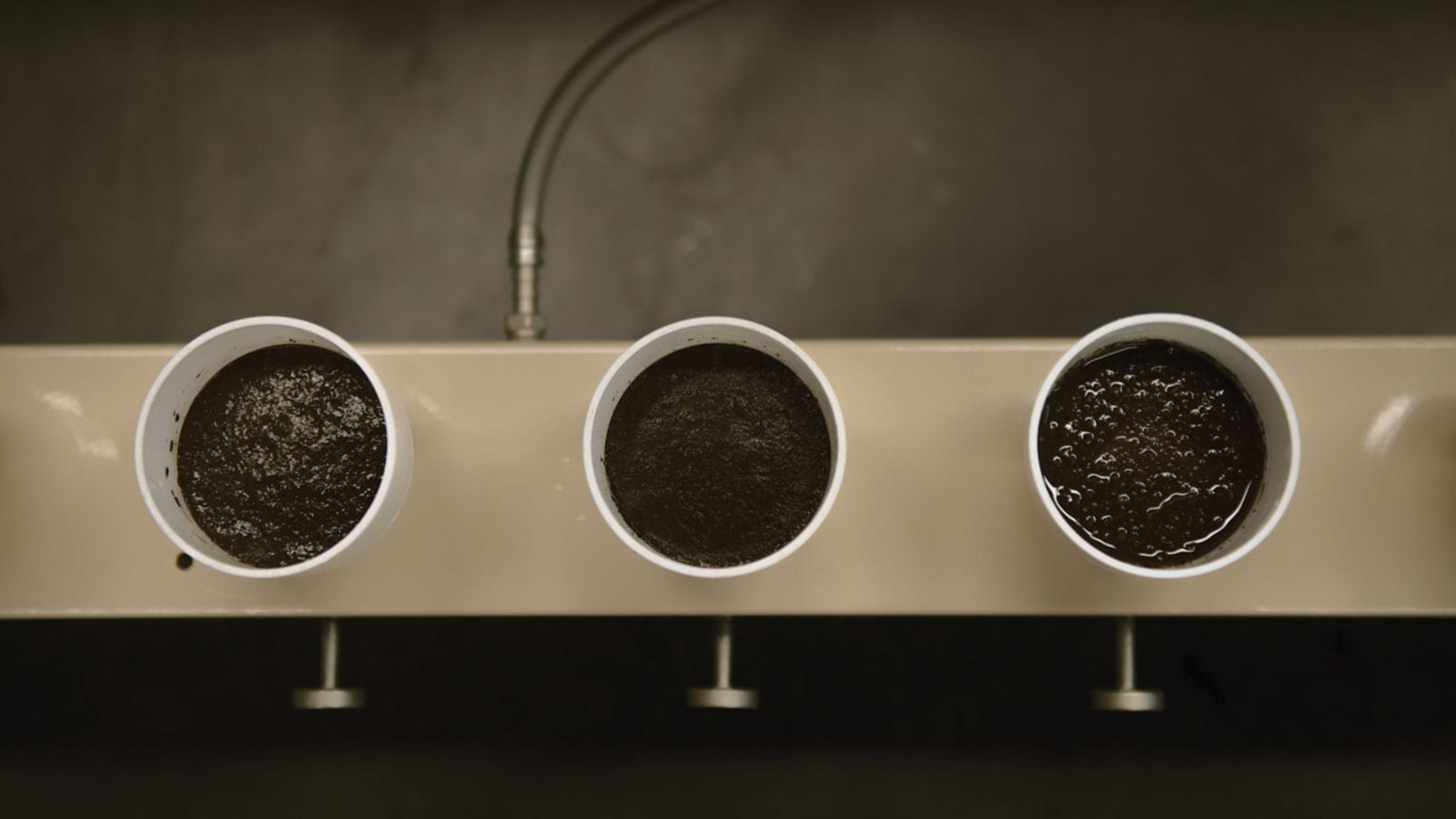

Charcoal use in farming has become a major research topic around the world, with thousands of academic papers published each year. Known as biochar when applied in gardens or farmland, charcoal has illustrated the potential to provide a series of soil health benefits and the ability to sequester carbon for thousands of years.

History lessons

In 2015, Forage, a sustainability research nonprofit, partnered with the University of Washington to conduct biochar research on 10 local farms in the San Juan Islands. The test results were compared to the soil of a historic Salish Camas garden on Waldron Island.

While the 10 farm soils received organic fertilizer every year over the past 20 years, the Camas garden received only a few piles of seaweed from the beach. The soil in the Camas garden, however, tested higher in nutrient retention than any of the traditional farm soils and was so black from historical charcoal applications that it took days to wash the color off the researchers’ hands. Some of this charcoal likely dates back thousands of years.

Charcoal is comprised of mostly recalcitrant carbon that can be stable for up to 10,000 years. Historic sites in Europe and the Amazon also illustrate that charcoal amended in soils can improve nutrient retention, biological activity, and carbon levels, with some of this charcoal introduced into the soil up to 7,000 years ago.

This long-term approach to sustainable farming comes at a time when a third of the world’s fields have been degraded by modern agriculture. Basic to this degradation is carbon depletion, with 50 to 70 percent of the world’s agricultural soil carbon off-gassed into the atmosphere due to tillage. This agricultural carbon loss has contributed nearly a third of the total carbon dioxide into the atmosphere since the industrial revolution.

Carbon is a core element of soil resiliency, in part because it is the food source for the soil microbiome. Soil bacteria serve a similar role to the microbiome in our digestive systems, breaking down nutrients so they can be absorbed more easily by plant roots, just as intestinal flora digests our food and makes it available to our bodies.

As this nutrient processing occurs, these minerals are transported through fungal systems to the plant roots. But, as carbon is lost, so too are the bacterial and fungal systems that help plants access and assimilate nutrients. The result is akin to humans losing the ability to digest food well — you require more food and still feel malnourished. Carbon is important for other areas of soil health, too, such as structure, aeration, water and nutrient retention. It’s the foundation of the soil ecosystem.

International research has found that charcoal may play a central role in regenerating carbon in degraded cropland. A 2014 academic study found that charcoal reduced carbon off-gassing by between 65 to 69 percent, a phenomenon termed the negative priming effect. This means that between 65 to 69 percent of the carbon already in the soil was not off-gassed.

The negative priming effect later was confirmed by a meta-analysis examining 395 research publications on charcoal and carbon off-gassing. It found an average 40 percent decrease in carbon off-gassing, known as respiration, and an average increase of 18 percent of microbial biomass.

Soil nutrition

The 2015–2016 San Juan County local farm biochar research project confirmed findings similar to the international research, with biochar increasing carbon levels between 35 to 40 percent.

In 2016 we discovered a 46 percent increase of active soil biology in biochar-amended soils. This increased soil carbon also keeps greenhouse gases out of the air, as nearly 50 percent of the carbon is stabilized for millennia in the process of converting to charcoal.

Making charcoal replicates a natural carbon storage process that historically occurred through forest fires. There are a series of additional soil health benefits, including significant nutrient and water retention in the topsoil that keeps fertility near the plant roots instead of leaching into the local aquifer, saving farmers money and limiting pollution of agricultural runoff.

As crops increasingly are exposed to unpredictable weather patterns in a changing climate, this spectrum of soil health properties can increase the health and resiliency of crops to these environmental stresses.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts that drought and flooding conditions will increase around the globe in the coming years, which could decrease crop yields by up to 17 percent by the year 2100. Regenerative agricultural practices, such as the use of biochar, will play an essential role in providing a supportive ecosystem that still can allow plants to thrive in severe conditions.

What you can do

It can feel difficult to find ways to address climate change in our own lives. Our personal lifestyle choices can feel insignificant compared to the magnitude of the Earth’s problems.

Using biochar in our gardens is one way of contributing positively. Charcoal sequesters carbon from the organic matter it is constructed from and keeps it in your garden’s soil and out of the atmosphere. It also is a way to invest in the long-term health of your garden soils, introducing a product that may improve fertility for generations.

If you would like to become part of this historical Pacific Northwest tradition of adding biochar to your soil, look for biochar at your local gardening store. It is most beneficial to add biochar continually to soils, though even a one-time application still will provide benefits for hundreds — perhaps thousands — of years.

Apply it at a rate of 2.5 gallons per square meter, or a quarter gallon per square foot. It also is good to add fertilizer to the biochar before introducing it to the garden. You can mix equal amounts of fertilizer and charcoal, applying it into the top three inches with a rake or hoe.

Now you have kept carbon where it belongs — in the soil and out of the atmosphere.

Kai Hoffman-Krull is the executive director of Forage, a sustainability research nonprofit, currently working on studies and education for plant resiliency in a changing climate.