Unmasking Food Industry “Barons”

This article was originally published in June 2024

Austin Frerick noticed something strange about his home state of Iowa. The pigs he used to see in barns and fields dotting the landscape had vanished from public view, packed instead in windowless sheds holding as many as 2,500 animals apiece.

The answer to the mystery, he found, was one man’s company, a confined-animal business controlling a stunning 5 million pigs per year, linked to pollution, health hazards and downgraded quality of life for Iowans as well as their hogs.

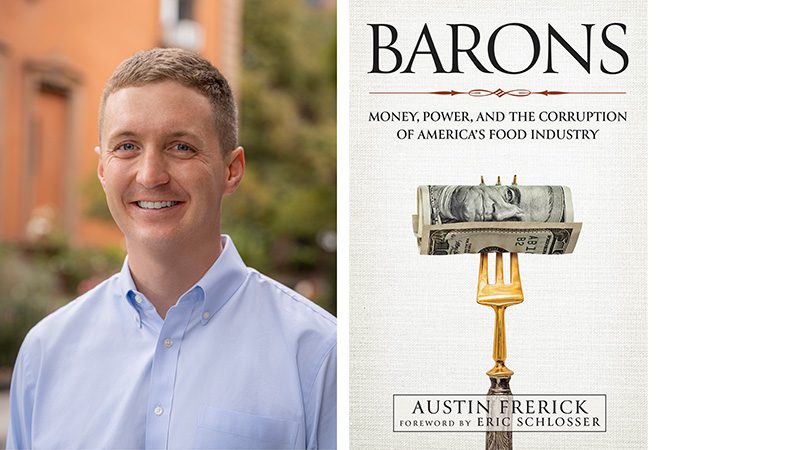

In his eye-opening new book, “Barons: Money, Power, and the Corruption of America’s Food Industry,” Frerick tells the story of that business and six others in a modern Gilded Age, monopolizing industries from pork to berries to dairy cows to coffee. Most are not even producers, but overseers in a 21st-century version of landowners and sharecroppers.

“That’s the scary thing, the food system in America is reverting to its really dark, exploitive origins — because we’re allowing it to,” he told Sound Consumer Managing Editor Rebekah Denn in a recent conversation.

Although monopolies are common across the economy, Frerick says few sectors are more consolidated than the American food system. It’s been corrupted, he wrote, controlled by industry barons who built empires “by taking advantage of deregulation to amass extreme wealth at the expense of everyone else.”

In years of research, Frerick said, he’s come to believe that the system will change and the pendulum will swing back.

“What you realize is, most people are good people. There are people that are trying to do the right things. You really just have a few greedy men holding us back.”

And greed, he said, always goes too far.

Frerick and Denn discussed Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, industry “Chickenization,” and why we shouldn’t lose hope. Frerick will join PCC members in a virtual book club event Oct. 22 (see below), here are more edited, condensed excerpts of their conversation:

Which of these Baron stories surprised you the most?

A: Because they have such a good public image, the milk one, the dairy one (industry giant Fairlife, which faced an animal abuse scandal and lawsuits). That’s more that they got so much good press for being “sustainable”…How much success they had cultivating a bullsh*t narrative really blew my mind.

For me it was the coffee companies, that Peet’s, Stumptown, Green Mountain, Panera are all part of the same corporation. I’m a coffee person and I never connected the dots there.

A: They make it really hard.

That chapter was the hardest to write from a narrative perspective, because it’s not linear. We literally went from Panera to Nazis (the family behind the parent company was led in the 1930s and 1940s by “enthusiastic Hitler supporters,” according to The New York Times). I wanted to explain not just the antitrust issues, but the role between monopolists and fascism.

Your book says individual choices, like buying from a small local farmer, will not solve the food industry’s problems, that fundamental solutions must “directly challenge power.” What does that look like?

A: We should end the consumer welfare standard, a failed approach that is inconsistent with the purpose of antitrust laws and that makes it nearly impossible to halt a large company’s accumulation of power. We need to enact brightline rules too that prevent barons from using their dominance to establish control of one sector or to expand into others. One example of such a rule is a ban against meatpackers raising the animals they slaughter. We should also prohibit large meatpackers from competing in more than one line of protein.

That said, you should push your local school or another institution to buy locally. It’s a great way to drive the development of the sort of food system we want to see because these institutional buyers buy a lot. Schools in particular spend a lot of money on food, much of which goes toward unhealthy options purchased from huge corporations. The substantial dollars and reliable contracts that schools and other institutions provide would be a game changer for many local and sustainable producers who are struggling to compete with the big boys.

One of the big things I’ve learned in writing this book was, everything we eat is subsidized to a degree. Right now we’re subsidizing junk. And you can use your fork to buy a local vegetable, but you’re always running uphill, and at some point, you’re going to run out of steam.

So how do we make political change?

A: For people in the Pacific Northwest, where are your members of Congress on these issues? They’re in safe Democrat seats, yet they’re not really in the conversation. A few Congressional folks do good work on this issue but everyone else pretty much votes in the interests of corporate America at this point.

That speaks to the powerlessness people feel about a lot of things, even beyond food.

A: That’s why I was very intentional that the first thing you see when you start my book is you meet this woman, Julie Duhn, you meet someone fighting back against a robber baron…

(The corporations) win the second you give up. Part of using this robber baron framework for people was showing that we’ve been here before, and we’ve dealt with this before.

In the book you mentioned your college thesis on the meatpacking industry. Did that work send you down this research path?

A: I first did it on the schools. What put them on my radar was, these slaughterhouse towns in Iowa, mostly in rural communities, are in the most diverse parts of Iowa, with very high free/reduced lunch rates… So I spent a summer talking to mayors, superintendents, teachers, clergy members in these communities asking what can be done by the schools to help them. I was interviewing a principal in one town, and in one sentence he was complaining, because he has a very high poverty population, about all the additional services they have to provide to their students because of those issues. But then in the next sentence he says how great the slaughterhouse is, because he gets free hot dogs for Back to School night. I was 22. At the time, I didn’t realize (the significance) and my professor was like, “You see, he can’t connect the dots. His issues would be solved if his workers were paid a little bit more, if the farmers were paid more.” So I did a whole second thesis just on power dynamics. And these towns are modern-day company towns. Not only are they the only players in these areas, a lot of these workers are undocumented. So there’s this very complex abuse of power dynamic at play.

You talk about when Upton Sinclair’s “The Jungle” was published in 1906, exposing the meatpacking industry. People learned what the system was like, they were horrified, and the system changed. And here you and others are, telling us what the system is like, and we are horrified. Why don’t we also get meaningful change?

A: When I read that chapter, my anger is with (U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom) Vilsack… To me, it goes to show that personnel is policy.

So if we get a different person overseeing the right department, things would change?

A: I really do think that.

If there’s one graph I could include in my book it would be beef prices. Consumers are spending more and more for beef every year, but what the rancher (earns) flatlined, and it’s just classic monopoly right there. The politics are so good here, someone will eventually solve it.

It also helps that these aren’t even American companies… a lot of these are foreign-backed state monopolies…

The tide is turning. The fact that you have all these Silicon Valley monopoly cases going on, that’s huge. And you’re not gonna stop them overnight. Teddy Roosevelt didn’t break up the meat companies overnight, that took years. It took heightening public awareness, and then you saw the government follow through in court cases that took years.

It’s all cyclical. If you’re a corporate executive, you want a monopoly, for profits. At some point, the markets get too concentrated and we have a cleansing moment and enter a reform era.

Did we used to be better, or did we have better guardrails?

A: I would say so. Even political appointees used to be better. The other thing I wanted to (highlight) was the checkoff section in the dairy, (programs where farmers pay into a fund to promote the industry, e.g. the Got Milk campaign), because to me, that is really what’s driving the corruption of the American food system. It’s creating that revolving door at USDA , and it’s neutering reform efforts.

I joked to someone yesterday that chicken is kind of the root of all evil in the modern American food system. We wrote these regulations a century ago. We didn’t write chicken into the regulations because there weren’t commercial chicken slaughterhouses, you just had chicken in your backyard and butchered them. So what happened in the South is, you see that sharecropping model applied to chicken production. And then chickens have gained market share because (farmers are) engaged in an exploitive production model. Then USDA could have stepped in to have chicken (treated) like the other meats, but instead you just see this race to the bottom across the food system. Call it “Chickenization,” where pork went that way and dairies are even going that way.

You wonder, if a certain person was in the right place at the right time, if we could have stopped that.

What else should people know?

A: Industry will always say, “Oh, this system is cheaper for Americans!” and that’s just not factually true. When you pull the data, per capita, Americans spend more on food than most Western democracies.

PCC Reads with Austin Frerick

Austin Frerick will join PCC members Oct. 22 for a virtual book club, speaking with Sound Consumer Managing Editor Rebekah Denn and answering your questions. In a special collaboration with The Book Larder, the first 20 PCC members to order the book through this link by July 15 will receive a 25% discount.