Fulfilling dreams with the United Indians of All Tribes Foundation

This article was originally published in March 2023

In legends, the Daybreak Star is a living plant, the blossoming “herb of understanding” that shines rays of light from soil to heavens.

In Discovery Park, its namesake building is home to United Indians of All Tribes Foundation (UIATF), a nonprofit organization providing social, cultural, and educational services for Indigenous people in the Puget Sound region. The 20-acre property includes walking trails, tall trees favored by nesting eagles and visiting woodpeckers, and—befitting the center’s name and purpose—a garden.

UIATF, a PCC partner since 2019, was founded in 1970 when members of various tribes occupied Ft. Lawton, an Army base that was being decommissioned. Led by the late Bernie Whitebear, members fulfilled the peaceful occupation’s goal of creating a cultural home (Daybreak Star) and services on 20 acres of the former military land, opening in 1977. The foundation’s many programs now include an outdoor preschool, support services for Elders, home visits for families, homelessness prevention assistance, and a traditional medicine program.

In 2003 a carefully selected collection of plants and trees were planted on a slim horseshoe of land near the Daybreak Star building, named in honor of Whitebear, the renowned founder. Unfortunately, over the years, the plantings have become overgrown. Plans this year include helping clear the Bernie Whitebear Memorial Garden and restoring it as a hands-on resource, as a “shining spectacle” of the natural world, as executive director Mike Tulee put it. (See box for how to help.)

“Part of the original vision of (Whitebear’s) was educating people as they came in—not just on traditional names, but what purposes they serve, for people who come into our cultural arena and may not have an understanding of what we’re all about.”

A dreamcatcher built into a wooden bulletin board marks the garden’s boundary, where some of the original plantings still made their presence known despite encroaching blackberries and other invaders.

“In the garden exist rose hips that are totally harvestable,” said Sherry Steele, the foundation’s official accountant and unofficial all-around project manager, pulling a few of the cherry-sized fruits from the vines. A sign marked where the kinnikinnick shrub (also known as bearberry) once stood, but has since disappeared. Thankfully, there are fresher plantings on a new garden area near the center’s front doors.

Uniquely, kinnikinnick is used for ceremonial smoke for such tribes as the Peoria (Steele’s Tribe), similar to how tribal members in the Southwest might use sage. “We’ll use a mixture of pine and kinnikinnick to make a smudging to clean the air. You can burn it on its own, or you can mix it with rose hips and other local plants. You can also make a tea from it,“ she said.

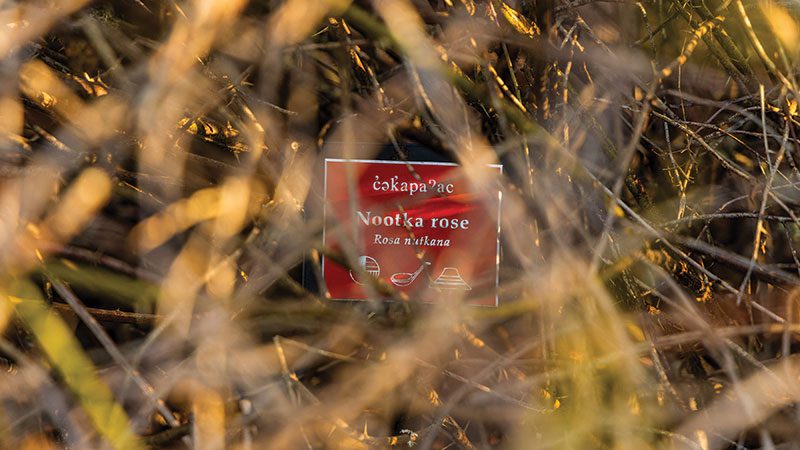

Each labeled vine or branch has its own story: Red cedar boughs are often hung over doorways as a symbol of welcoming and good energy, Steele said, while the bark can be medicinal. Oceanspray, puffing out clusters of white flowers in the summertime, has disinfectant properties and can be used to make soaps and shampoo. Serviceberries, salmonberries, elderberries and stinging nettle are all marked among the garden’s nine zones in an educational map. The garden signs also reflect Native names (usually in Lushootseed) along with common and botanical names. Some 90 species of culturally important plants were marked for the original garden, with some used for crafts and fiber, some for food, some for medicine and ritual, all part of Whitebear’s vision of revitalizing traditional knowledge.

It’s hard to overstate Whitebear’s legacy, whether it was supporting tribal members living in the Puget Sound region or in making their history and presence visible to non-Natives, too. A pivotal figure in the national battle to protect treaty fishing rights for Native people, he was also the first executive director of the Seattle Indian Health Board and served on the board of the National Museum of the American Indian.

“Our programs, services and even the garden are designed to provide past, present and future educational and cultural tools for all to learn about and enjoy and preserve,” Tulee said. A restored, replanted garden is one more facet in an array of services both on land and off for the Native people in all walks of life here. The foundation also sponsors an annual Seafair powwow that’s open to all, a youth transition home in Greenwood, a canoe carving house, part of the Northwest Native Canoe Center, recently breaking ground in South Lake Union, and an internet radio station that plays 97% Native music.

Additionally, a replanted garden would be a step toward another greater goal: Food sovereignty.

“If you go to a reservation, all around the outside will be fast food. There is usually not a grocery store at all,” Steele said. United Indians works to provide nutritious food for tribal members as an important foundational goal. But an important step beyond that is to help provide culturally relevant and nutritious foods.

Two garden areas by the Daybreak Star doors have already been landscaped with meaningful plants, and the Whitebear garden will hopefully soon follow. Within the park, near Daybreak Star, by planned affordable housing that United Indians will help develop, Steele pictures even more possibilities: “to have things that people could touch and see and feel and know are real.” Adding beehives for honey, for instance, is “one of my little dreams,” she said.

They’ve already fulfilled so many, but there’s room for more to come.

Join the campaign

PCC’s spring fundraising campaign will benefit United Indians of All Tribes Foundation, one of its many nonprofit community partners. Learn more about the organization at unitedindians.org and join in by:

Interested in helping maintain the Bernie Whitebear Memorial Garden? Sign up here for that or other volunteer opportunities with the United Indians of All Tribes Foundation.

PCC has partnered with United Indians of All Tribes Foundation on a tote bag by Pacific Northwest-based Indigenous artist Heather Johnston. The tote will be available at all PCC stores and a portion of proceeds will go to the foundation.

PCC’s spring fundraising campaign at all stores from April 5 through May 31 will benefit United Indians of All Tribes Foundation. Donations can be made at the register or online here.