Grocery story: How food co-ops transformed an industry

By Jon Steinman, guest contributor

This article was originally published in July 2020

Who owns your grocery store? In the case of co-ops, it’s the members. Author Jon Steinman looked at their fascinating history in his recent book, “Grocery Story: The Promise of Food Co-ops in the Age of Grocery Giants” (New Society Publishers, $19.99). The excerpt below covers the waves of food co-ops that formed in America starting in the 1930s and is reprinted by permission.

The “food for people not profit” mantra is a principal feature marking the waves of food co-op formation in North America.

Whereas the first wave of consumer co-op activity leading up to the Great Depression was generally led by the labor movement, a new movement gained strength between 1930 and the 1950s, this time led by consumers. The cooperative movement began to see consumers, not workers, as central to social change.

The Consumer Wave

The labor movement’s interest in consumer co-ops continued into the 1930s, particularly as a result of the Great Depression. Membership in consumer cooperatives doubled between 1933 and 1936.

As a distinct movement from other food co-op development, African Americans were also successful in establishing co-ops as an instrument to rise above the economic struggles of a segregated nation. W.E.B. Du Bois believed self-segregation would be necessary to achieve equity for black Americans. For Du Bois, retail co-ops could be what he referred to in 1917 as the “economic way out, our industrial emancipation.”

In 1934 in Gary, Indiana, a successful African American buying club was formed and within three months had become a fully fledged grocery store. The Negro Co-operatives Stores’ Association had 400 members in their first year and did more business than any other black-owned retailer in the country.

Housing projects in 1930s Harlem also became home to food co-ops like the Pure Food Co-operative Grocery Store that in 1934 was owned by 350 Harlem families. In one case, a Harlem food co-op was so successful, the local A&P was forced to close.

Meanwhile CLUSA welcomed the Roosevelt administration’s efforts to reconstruct the economy by placing increased power into the hands of consumers, but saw it as only a short-term measure to “ease the pains of poverty” and “give time for thinking things through and organizing the new cooperative economic order.”

At American colleges and universities, interest in the study of cooperatives grew and is likely why many consumer co-ops began to appear in college towns. Some of the more notable co-ops were connected to the University of Chicago (1932), Cornell University (1932) and Dartmouth College (1936). In Dartmouth’s home of Hanover, New Hampshire, 17 families (mostly Dartmouth faculty) formed what would become the Hanover Consumers Co-operative Society. Unlike many Depression-era co-ops, Hanover continues to this day as one of the largest and most successful food co-ops in the country.

After the war, 2.5 million people across the United States had become members of retail co-ops. The thrust of the movement, however, began to change. In its vision for a cooperative commonwealth, CLUSA began to scale back its approach. Instead of replacing capitalism, the movement would set its sights on challenging the monopolies and would do so as a sector co-existing within a capitalist economy. As the first co-op supermarkets began to appear, the grocery giants sensed a new threat. The chains launched attacks on food co-ops, calling them “un-American, subversive and communistic.” One newspaper headline read, “Retailers Plan Nation wide War on Co-ops.”

Just as the big grocers used low prices to drive out the smaller independents, co-ops were not immune to their wrath. Many co-ops failed. CLUSA’s director in Washington, D.C., said that the failure of co-ops was the result of them “competing against a false price level established by chain stores.”

While many co-ops failed, many prospered. By the 1950s, there were 20,000 co-ops with 6 million members. In San Francisco, one quarter of the population were members of the Berkeley Food Co-op.

In their efforts to grow, remain relevant and compete, many food co-ops in the 1950s began to resemble their capitalist counterparts. It was hard to distinguish old-wave co-ops from supermarkets. Member participation in the co-op democratic process decreased, and many co-ops across the globe entered into what John Restakis calls a “phase of conservatism.”

In Canada, this era brought about what today is the country’s largest network of consumer co-ops—Federated Co-operatives Limited (FCL)—while the now-defunct Co-op Atlantic became a strong force in Canada’s eastern provinces. Whereas the 1970s co-ops operated on a parallel course to the conventional chains, the mid-century co-ops competed head-on.

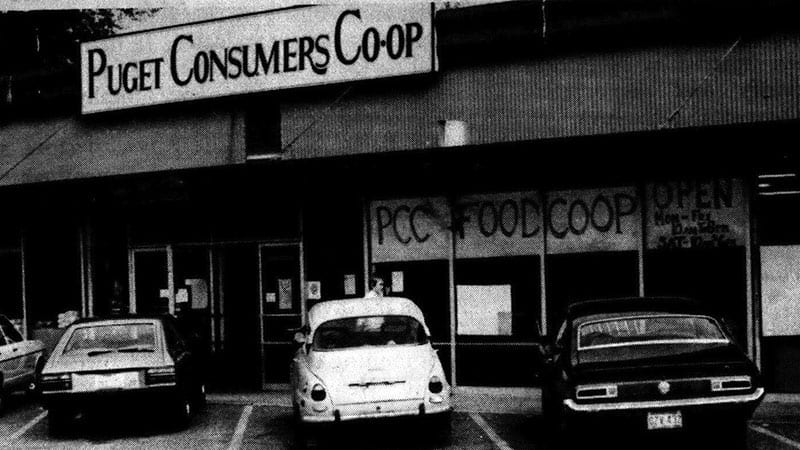

In the United States, one food co-op that got its start in 1953 stands on its own. The Puget Consumers Co-op of Seattle (PCC) began as a buying club of 15 families and would grow to become a leader in the natural food co-op movement. In 1967 PCC opened its first store, marking the beginning of what today is known as “The New Wave” of food co-ops.

The New Wave

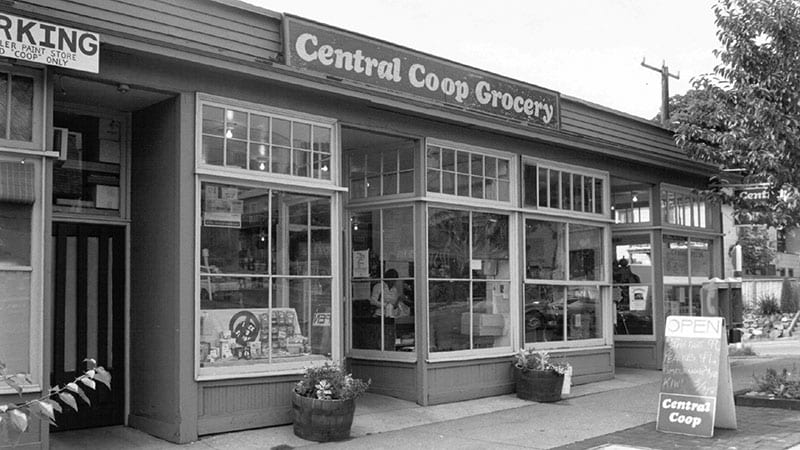

Whereas the 1940s through ’50s saw a transition of food co-ops from being a working-class movement to a middle-class movement, the late ’60s through ’70s marked the entry of a new and predominantly middle-class and price-conscious cooperator—the counter culturalist. This new wave of community-owned grocery stores would end up playing an important role in the growth of the organic, fair-trade, and local food movements and would increase public awareness of healthy food, food quality and many food issues. The largest and most successful community-owned grocery stores in the United States and Canada today are mostly a product of this counter-movement. An estimated 5-10,000 food co-ops (or “food conspiracies”) were started in the 1970s.

Out of the prosperity of the ’50s and ’60s came a number of well- organized resistance movements to the economic, racial and gender disparities of the time. Civil rights, women’s rights and the anti-war movements had created a highly organized counterculture. Two other significant global events deepened the counterculture’s commitment to food as an engine for change: the end of cheap energy precipitated by the OPEC oil shock, and the global food shortage caused by the devastating harvests of 1972 and 1974. Like their earlier 20th century revolutionary counterparts, the ’60s and ’70s revolutionaries began to envision economic systems that would replace capitalism. But the next wave of food co-ops wasn’t driven entirely by the desire for a new economic order. The 1960s was a time of increasing awareness of diet and nutrition, and many had begun turning to vegetarianism and unprocessed whole foods. Privately owned alternative natural food stores served this new demand, but their prices were high.

To secure greater control over their food while ensuring it was nutritious and affordable, people organized food co-op buying clubs and storefronts across the U.S. and Canada. “You could go to an antiwar meeting and then go to a food co-op discussion and half of the room were the same people,” says longtime food co-op leader Dave Gutknecht. In one case, the People’s Food Co-op in La Crosse grew out of a class on whole foods at the University of Wisconsin.

Most co-ops were initially financed with little capital. Access to traditional forms of capital was hard to come by. Commercial lenders were hesitant to lend to zero-profit cooperative businesses. Over 60% of established co-ops at the time were refused financing. Most relied on truly bottom-up democracy and depended upon members for both financing and labor. Member labor kept prices low.

Co-op buying clubs and storefronts came to support craft food production, organic farming and provided healthier alternatives to highly processed “corporate food.” Food was the vehicle for a new way of life. “Selling food isn’t our goal, it’s just a pretext for building, living and breathing models of revolutionary change,” said one member of Washington, D.C.’s Field of Plenty Co-op of the late 1970s.

The New Wave co-ops became progressive neighborhood community centers. Outpost Natural Foods Co-op in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, was open 24 hours a day, “not just to sell more food, but because people wanted a place to hang out,” says founding member Steve Pincus. “There was often a faint odor of marijuana, and the spacey checkout clerks sometimes made incorrect change.” For many food co-op founders, food would become the ground zero from which society could be transformed. “We wanted to set up an alternative, parallel system to just about everything, and food was a good place to start.”

The governance of the early co-ops was haphazard, often intentionally so. They rejected the supposed benefits of formalized structure for the “intimacy of spontaneously occurring and situationally flexible leadership.”

As hubs of community activity, food co-ops often became the only places providing the economic and political resources for groups working on strategies for alternative living. They became the best place for “leaflets, collecting signatures and discussing issues.” They were highly social environments. When researchers studying food co-ops in 1982 approached shoppers at both co-ops and supermarkets for interviews, customers at supermarkets “were more likely to avoid eye contact and walk away when approached.”

To facilitate the rapid rise of co-op buying clubs and storefronts, distribution co-ops were established to increase buying power of the individual co-ops and to centralize food storage and distribution. Iowa’s Blooming Prairie Co-operative Warehouse of 1976 would eventually service food co-ops in five states and offer direct support to groups interested in starting co-ops or transitioning from a buying club to a storefront. Many of the distribution co-ops were owned by the individual co-ops being supplied.

The importance of new food co-ops to the ideologies that spawned them is best captured by the violent clashes that took place in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis–St. Paul between rival factions of cooperators. Yes, an oxymoron! In one case in 1975, food co-op organizers battled over control of the People’s Warehouse—a food co-op distributor. On one side were the anarchists, on the other, the communists. The firebombing of a delivery truck, Molotov cocktails through the window of Bryant Central Co-op, a violent takeover of Seward Co-op—the formation of food co-ops in the Twin Cities was impassioned, albeit an isolated extreme among food co-op formation. Cooperative combat aside, the Twin Cities and surrounding communities became a hotbed of food co-op activity.

The people generating such sources of power through food co-ops believed they were also actualizing something that was culturally appropriate. Similar to many of the co-ops of previous decades that had opened along ethnic lines, the cultural and social values espoused by the counterculture were simply not being met by conventional grocers.

The New Wave Grows Up

By the late ’70s, many buying groups had begun to merge.

Once the early ’80s had arrived, many food co-ops found themselves at a crossroads. Many co-ops had already grown into successful businesses with managers and boards of directors, while others had retained strong opposition to any formalized structures that resembled capitalism. Paradoxically, the non-model approach to cooperation was seen by many as anti-democratic compared to more formalized models of intentional planning, delegation and consenting of decisions. The participatory management approach resulted in meetings dragging on “interminably” with “nothing seeming to be settled.” “The same issues arise, get discussed, voted upon, only to appear again in the same or another form.” This level of dialogue strengthened the co-ops but also contributed to member burnout. The need for change was in the air.

In a 1984 article in The New York Times, Ron Cotterill, a professor of agricultural economics at the University of Connecticut, proclaimed that the “general blush of social and cooperative spirit that was present before 1980 is gone.” Cotterill believed it was time for co-ops to become more “practical” and “businesslike.” The greatest threat to co-ops at the time was themselves. “You can’t be an economic alternative if you’re not around,” said food co-op leader Karen Zimbelman in 1985. If the co-ops could not make it, the alternatives to eaters were the conventional supermarkets. Many co-ops chose to avoid such demise.

For those willing to evolve, this was no easy transition. Co-ops would need to balance the ethics and values of their members with the realities of running a business. The early new wave co-ops had kept food prices remarkably low, thanks to the energy and effort of volunteers who carried out tasks that would otherwise have been performed by paid labor. To keep prices low, many co-ops maintained their roots as “participatory co-ops,” requiring members to commit labor to the functioning of the store. Many of these co-ops had evolved to have paid managers, but with on-the-floor tasks performed by members. The participatory approach was effective at keeping prices down—generally 25% lower than conventional stores.

Some co-ops made member labor a requirement, while others made it optional. Choosing to invest one’s time granted access to lower prices. An estimated 3,000 of these participatory co-ops existed in 1982. Not surprisingly, requiring member participation at co-ops was precarious. Most co-ops who emerged successfully out of the era relied completely on paid labor, or made member-labor optional.

This era of change reduced the total number of food co-ops in the country, but total volume of sales among co-ops remained steady. Some of the co-ops that had weathered the period chose to open up second and even third stores, like North Coast Co-op in Arcata/Eureka, California, and PCC.

Modernizing co-op stores with cash registers, refrigeration, management teams and boards opened up new possibilities. With stronger frameworks in place for running a grocery store, co-ops could expand their creative potential and begin to truly develop their bigger picture visions—particularly, placing greater attention on the foods they were selling. Their power to effect change was strong. Co-ops boycotting products was not uncommon nor was the introducing of previously restricted foods. With many co-ops having grown up as vegetarian stores, some began to introduce meat. The Brattleboro Food Co-op in Vermont held a referendum in 1985 with members voting 51% in favor of carrying meat. At the Wedge Community Co-op in Minneapolis, convenience foods and frozen dinners also began to appear on the shelves.

The co-ops that made it into the ’90s had deservedly entered into a period of abundance. Interest in vegetarianism and organic food was growing, and co-ops were well-positioned to serve this rising demand. Conventional stores, on the other hand, were not yet prepared to compete on these products and knew very little about this peculiar market of conscientious consumers.

The Newest Wave

There was very little new food co-op development in the 1990s and early 2000s, but many existing co-ops thrived.

As the new century commenced, so did increased awareness of food politics. With it came a renewed interest in the model of community-owned grocery stores, and another wave of food co-op formation followed.

Once the local food movement took hold, interest in co-ops exploded. To nurture and support this wave of interest, organizations like the Food Co-op Initiative (FCI) were formed with the support of the national food co-op sector. FCI focused on organizing the movement, CDS Consulting conducted planning and feasibility studies for co-ops, and National Co-op Grocers’ development co-op focused on operations. Between 2008 and 2018, 134 new co-ops opened in the United States with a 74% success rate. This represents 160,000 new member-owners of community-owned grocery stores nationwide. As of 2019, another 100 are in the works.

The most surprising feature of the newest wave of co-ops has been their resilience through an incredibly challenging economic climate. Natural food chains have burst onto the scene, and conventional chains are dedicating more square footage to many of the same foods that co-ops have traditionally carried. The success of many co-ops in this new competitive climate indicates that there’s something different about co-ops that draws eaters’ interest.

Beyond Natural Foods—Co-ops for Low-Income Communities

Joining as a part of the newest wave are two new breeds of food co-op.

In one new stream are co-ops offering a blend of conventional and natural foods. In another stream is an interest among communities that find themselves in “food deserts”—low-income neighborhoods devoid of any full-service grocery store whatsoever. Difficulty accessing a nearby full-service grocery store may exist in any neighborhood regardless of income levels, but the impact among low-income communities is considerably greater due to the comparative lack of access people with limited financial means have to transportation. There are inspiring stories of food co-ops being established in food deserts and in mixed-income neighborhoods lacking easy access to healthy food.

Whether one lives in a low- or high-income neighborhood, an urban center or rural countryside, or whether one shops for conventional or organic foods, grocery stores owned by their shoppers hold the possibility for all people to democratically control access to good food.