The unexpected consequences of antibiotics

by Debra Daniels-Zeller

This article was originally published in August 2014

Hailed as heroes for saving millions of lives during World War II, antibiotics worked so well by the 1950s that if one antibiotic didn’t work, other options were available. Resistant threats loomed far off on the horizon. Side effects to health were assumed to be short-term.

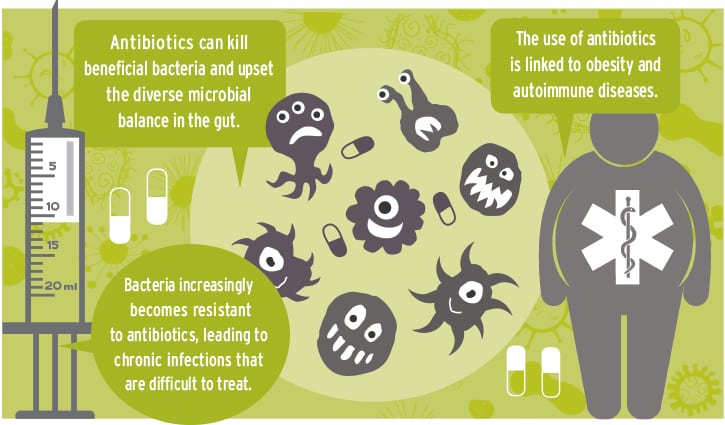

The collateral damage antibiotics could do to our microbiome — the trillions of microbes living in our gut — is just being discovered. Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, asthma and obesity are just a few of the increasing chronic health problems linked to antibiotics.

The drugs may have a bad reputation today, but imagine a time when a simple scratch could kill. What we consider minor illnesses and injuries were death threats before Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin in 1928. First used in 1943, penicillin saved up to 95 percent of soldiers with infected battle wounds in World War II. In 1944 an advertisement in Life magazine said, “Thanks to penicillin . . . he will come home.” In 1943 tuberculosis was treated effectively with streptomycin. Scarlet fever became rare because of antibiotics that also paved the way for successful organ transplants.

Creating resistance

Many people thought antibiotics could do no harm, but in 1945 Fleming warned about the dangers of under-dosing and causing antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Just three years after penicillin first was used, resistant bacterial strains surfaced.

Resistance happens when bacteria changes and develops armor-plated cell walls that antibiotics can’t penetrate. Overuse of antibiotics encourages resistance and, as resistance spreads, the fewer antibiotics will be available when we need them.

In the late 1940s farmers found that antibiotics allowed livestock to gain twice as much weight as their drug-free counterparts. In 1951 the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved antibiotics for livestock for disease prevention and growth promotion. Even Fleming couldn’t have predicted the magnitude of problems created by antibiotics on factory farms.

Researchers continued to warn about resistance through the 1970s. A study from Tufts University about resistance on chicken farms in 1976 led the FDA to propose a ban on penicillin and tetracycline in farm animals in 1977. Farmers and drug manufacturers opposed the rule. It never was enforced.

Sweden banned antibiotics for farm animals in 1986. The European Union supported a ban on the antibiotics used for farm animals in 1999.

A recent U.S. government analysis of 30 antibiotics in livestock feed said more than half of them are likely to contribute to resistant infections.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has said resistance is a major health threat to everyone, with more than 2 million people sickened and 23,000 fatalities each year. The World Health Organization warns that antibiotic-resistant infections could derail the “achievements of modern medicine.”

As superbugs make headlines, the connections between our microbial world and antibiotics are just being revealed.

Our microbial world

Microbes, including bacteria, were one of the first life forms on the planet. Microbes created the air we breathe and fill every niche on the planet. Some microbes have a lifespan of less than an hour, while others have been found alive after half a million years, living in suspended animation under permafrost in the Yukon. They fill oceans, survive deep freezes, and, carried by winds, microbes even have been detected 22 miles above earth’s surface where they help form clouds, influence weather and ultimately change landscapes. Microbes also can eat plastic, compost food waste and help us grow nutritious food.

Between 70 and 90 percent of the cells in and on our bodies are microbes. Our microbiome continually is influenced by environment, diet and drugs.

More than 500 types of bacteria live in the human gut. Most bacteria are harmless, some are beneficial, and some are shifty characters, such as Clostridium difficile (C. diff). After certain antibiotics, C.diff isn’t killed. Instead, it increases and dominates gut bacteria, creating toxins that attack intestinal walls. C.diff produces spores that go dormant for up to two years. Few antibiotics can treat C. diff because it hides and returns.

Balanced, diverse gut bacteria are a key factor in health.

Clues from the honeybee

For more than 50 years, many beekeepers used oxytetracycline in beehives to treat American foulbrood disease, a deadly bacteria that infects bee larvae.

According to Yale University researchers, honeybees across the United States now carry at least eight different tetracycline-resistant genes. These genes are not found in colonies in countries where antibiotic use is not allowed. Beekeepers adopted a new antibiotic, Tylosin, around 2006 — about the time Colony Collapse Disorder first was detected.

Evolutionary biologist, professor and honeybee researcher at the University of Texas, Nancy Moran, has studied honeybee microbiomes and says that prolonged exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics results in loss of bacterial diversity in honeybees. Carrying resistant genes has not been beneficial to honeybees and Moran suspects Tylosin may have altered bee metabolism and affected the way honeybees excrete pesticides.

If repeated doses of antibiotics affect metabolism in honeybees, could they do the same thing to us?

The obesity link

Obesity is a complex health issue. Microbe disruption by antibiotics is a new suspect to add to the list, according to Martin Blaser, author of “Missing Microbes.”

Farmers have known for decades that animals pack on pounds quickly when given antibiotics. Scientists aren’t sure how this happens but, like the honeybees, studies of mice reveal gut bacteria controls metabolism.

In the United Kingdom, a study of nearly 12,000 children found that children who received antibiotics in the first six months of life gained more weight than children who didn’t get antibiotics. Scientists at the Flemish Gut Flora Project in the Netherlands also found connections between low gut bacteria diversity and obesity.

A survey on obesity rates in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2010 found that obesity rates in the United States were highest in the states where most antibiotic prescriptions are written.

Thin people have a rich diversity of gut bacteria functions, unlike the low diversity in obese people.

Autoimmune links

A researcher in Valencia, Spain, found that just one dose of antibiotics makes all bacteria in the gut respond as if they were under attack. Like an army, the gut bacteria immediately produce defenses to keep the antibiotics at bay. Vulnerable bacteria die in the battle, and their functions shut down. Since 70 percent of the cells in our immune system are found in the walls of the gut, it isn’t surprising autoimmune diseases are on the rise with increased antibiotic use.

A study published in the Journal of American Academy of Pediatrics reported that antibiotics used in infancy might be a risk factor for developing asthma, allergies and other autoimmune diseases. People who live in developing countries have been found to have a wider diversity of gut flora than people in industrialized countries, and are much less susceptible to autoimmune disorders.

Blaser says antibiotic disruptions early in life can wipe out helpful bacteria such as Helicobactor pylori. This bacteria has been associated with stomach cancer, chronic inflammation and ulcers, but a lack of H.pylori has been found to be associated with asthma.

Early exposure to antibiotics in the first 15 months of life increases the risk of developing Crohn’s disease. One study found people who had Crohn’s were more likely to have received a prescription for antibiotics preceding their diagnosis. If a family history of Crohn’s exists, experts suggest antibiotics should be used only for verified bacterial infections.

The same goes for celiac, another autoimmune disorder with a genetic link. Researchers at Karolinska Institute in Sweden found a strong connection between antibiotic use and the onset of celiac disease.

Antibiotics can cure bacterial infections but overuse is hurting us.

Efforts to curb antibiotics

In 2013 the FDA set up a plan to stem the indiscriminate use of antibiotics for farm animals, but the plan is voluntary.

Residues of antibiotics in meat are considered minimal, because animals are required to wait a time between ingestion of antibiotics and being slaughtered, but according to the United States Department of Agriculture, meat, poultry, dairy and eggs contain antibiotic residues that have been detected since 1996. A poor showing on a residue test won’t trigger a recall because the government can’t show that a serving of meat would cause illness.

The Seattle City Council passed a resolution to support a statewide and national ban on non-therapeutic antibiotics in livestock. City councils in four other cities — Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Providence and Redhook, New Jersey — also have passed similar resolutions.

Antibiotics used liberally on factory farms make people sick. Unnecessary prescriptions make antibiotics less effective. In a recent New York Times article, physician R. Balfour Sarteo said, “My advice to parents and grandparents is “Let them [children] eat dirt.”

We may not need to eat dirt, but a little more respect for beneficial bacteria and a lot more caution with antibiotics would be a good start.

Debra Daniels-Zeller is a freelance writer and author of The Northwest Vegetarian Cookbook (Timber Press).