Easing stress through diet

by Tom Ballard, R.N., N.D.

This article was originally published in December 2011

Optimal nutrition can lessen the ravages of stress by reducing the chemical impact, repairing its damage, and preparing the body for future stress.

We live in stressful times. Economic uncertainty and other global problems can weigh on us heavily, and some of us have adopted high-stress lives with demanding jobs, vibrant families and too little sleep.

Stress often is referred to as “the silent killer” because of its widespread, insidious, negative effects on the body. Life stresses, for instance, reduce natural killer cells that are a vital part of our immune protection. Without a well-functioning immune system we’re susceptible to a long list of ailments.

Stress also increases inflammation, which, in turn, makes us more susceptible to chronic diseases.

Stress often is exacerbated during the holidays when family and travel can take a toll, so it’s important to find healthy ways of coping. Guided relaxation, yoga, hypnotherapy and other stress management programs are shown to provide valuable relief, yet they ignore the important nutritional aspects.

Nutrition can be a powerful tool for countering the negative effects of stress. PCC shoppers already have employed a stress-countering therapy, whether they know it or not.

Poor stress-coping behaviors

Our attempts to cope with stress often are nutritionally detrimental. A person may make poor food choices, grabbing coffee and sweets and other stimulants in a vain attempt to counter the fatigue that goes with chronic stress. Lack of appetite might lead to skipping meals or, conversely, nervous agitation may compel mindless munching.

Stressed people tend to crave fats, sugar and salt. Bad fat intake (French fries anyone?) further disrupts essential fatty acids and adds to the inflammation set in motion by the stress. Sweets tend to cause a rollercoaster effect on blood sugar — extreme highs and lows — and can trigger the release of more epinephrine and cortisol, hormones that help us cope with emergencies. Sweets also trigger inflammation. Inflammation is like a fire, and excess stress and a poor diet fan the flames.

Skipping water and sipping coffee can lead to dehydration. People on adrenal overdrive often don’t feel they have time to eat properly, so they grab and gobble fast foods, multiplying damage to their body. With mindless munching often comes more fat, sometimes triggering unhealthy crash dieting (not to mention more worry).

The stress response

Stress can be described as the body’s response to a life event. The event, or stressor, often is thought of as something negative, but it also may be a positive occurrence. Stress rating scales classify marriage as just as much of a stress as divorce.

Perhaps the best visualization of stress is the “fight-or-flight” response. Evolutionarily we responded to the stress of being attacked by a lion either by mustering our courage to fight, or screaming and running. Whichever choice we made involved the adaptation of our body to the new circumstances. Short-term stressors, such as the attack by the lion, actually can be good for us — they keep us on our toes, so to speak. Prolonged stress is what gnaws away at us.

Being attacked by the lion is one thing, but having it pacing just outside your cave day after day is another. It gets on our nerves and steals our focus. The inability to respond to a chronic situation is particularly hard on the body. It would be much healthier if we could quit the job we hate, or punch the badgering boss, but more likely we have to stuff our emotions and delay acting for weeks, months or even years.

Stress creates measurable responses throughout the body, increasing blood pressure, pulse and muscle tightness. Sleep suffers, the gut churns, the mind races and a host of internal chemical changes try to adapt. Basic functions such as digestion, tissue repair and reproduction all are placed on the back burner.

Stress hormones

Under stress the adrenal glands release epinephrine and cortisol into the blood, where they travel throughout the body.

Epinephrine (also called adrenaline) is a hormone and a neurotransmitter that works rapidly in the body — increasing heart rate, constricting blood vessels, dilating air passages — and participates in the fight-or-flight response. If you’ve ever watched a television medical show, you’ve heard someone call out for “epi” during an emergency. Epinephrine allows for a quick response to a stressful situation.

Cortisol is a steroid hormone made from cholesterol (yes, cholesterol is necessary for a number of functions). Cortisol has somewhat slower and longer-lasting effects than epinephrine. It helps direct the body’s response to stress, acting on other systems such as the nervous, muscular and digestive, as well as vision and even other hormones. If epi is the quick-responding palace guard, cortisol is the army summoned to take control and restore balance.

Our health is severely impacted by long-term stress (the lion pacing in front of the cave). In the case of an immediate threat that we can respond to, turning down other systems, such as repair and digestion, are entirely appropriate. You’re being attacked by a lion, so dinner can wait. Long-term stress, on the other hand, causes ongoing damage throughout the body.

Signs of adrenal fatigue

The assault of ongoing stress impacts our health in many ways. Fatigue and lack of stamina are common. Blood pressure rises early on but may become low as adrenal fatigue sets in. The hyper-vigilant response may be sensitivity to light, insomnia, anxiety and even panic attacks followed by periods of depression and loss of motivation.

Digestion falters, causing gas, bloating, diarrhea, constipation and heartburn (not from too much acid, but from inflammation). Levels of hormones such as thyroid, testosterone and estrogen initially may swing widely, then drop. Inflammation rises, causing muscle and joint pain, skin irritation, blood vessel damage, bone loss, allergies and other chronic health problems.

Nutrition against stress

Optimal nutrition can lessen the ravages of stress by reducing the chemical impact, repairing its damage, and preparing the body for future stressor attacks.

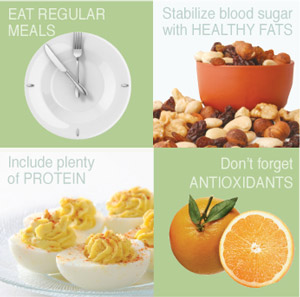

An easy way to mitigate the effects of stress through food is to eat regular meals and snacks with protein and fat throughout the day to maintain steady blood glucose levels. Meals should be small to not overtax the digestive system. Always eat a healthy breakfast starting your day with protein, good-quality fats and antioxidants. Also be sure to drink plenty of water — half your body weight in ounces every day.

Essential fatty acids from nuts, seeds, flax, fish and other food sources are important for several reasons. The omega-3 oils found in grass-fed meat and eggs, oily fish, flax and borage oil are anti-inflammatory to counter the pro-inflammatory effect of stress. Good fats also help stabilize blood sugar, lessening the roller-coaster effect that compounds the stress effect.

Protein is essential. It’s necessary for the manufacture of cortisol and for stabilizing blood sugar. It’s also useful for maintaining lean body mass. For more on protein intake see my previous Sound Consumer article, Protein: How much is enough … or too much?.

If you’re overweight, assess your lifestyle for ways to lose weight. Fat cells convert cortisol to estrogen, disrupting estrogen balance in both men and women.

Maintain good liver function because the liver acts to control circulating levels of cortisol and deactivate and eliminate “used” hormones. Fiber, water and probiotic bacteria (found in yogurt and other fermented foods) support proper liver function.

Avoid toxins such as synthetic additives and pesticides by eating low-processed, organic foods and avoiding unnecessary drugs.

Pesticides are another stress to deal with, and organics have been shown to have more repair vitamins and minerals. Eating sulfur-rich foods, such as broccoli and beans, and antioxidant-rich foods also supports the liver.

Antioxidants help counter inflammation, too, so eat plenty of foods such as organic fruits and vegetables (especially deep-colored ones), tangerines, turnips, green tea, cinnamon, oregano, soy, eggs and tomatoes. It’s best to obtain antioxidants from a range of foods rather than a single source.

Vitamins especially helpful for the adrenal glands include B vitamins from grains, beans, eggs, meat, and chile peppers; and vitamin C found in fruits, green leafy vegetables, melons, tomatoes, broccoli, and red and green bell peppers.

Magnesium is a mineral that supports a healthy immune system, helps regulate blood sugar levels and promotes normal blood pressure. It’s found in vegetables, dairy, meat, eggs, fish, seafood, nuts, tofu and whole grains. Salt can be helpful in maintaining blood pressure for those with low blood pressure. (These people often crave salt.)

Avoid sugar, coffee, alcohol and cigarettes. While tempting under stress, they disrupt blood sugar, hormone levels and neurotransmitters. When you do indulge, do so after eating a meal or snack containing protein and fat.

The takeaway

The general consensus seems to be that stress is a part of life and we just have to “live with it.” But we do have options; exercising, crying, laughing, yoga, tai chi and smart dietary choices help alleviate stress-induced disease.

Making “smart” choices, by the way, doesn’t mean food should be boring or tasteless — quite the opposite. Food is best when enjoyed, so embrace the best of your holiday traditions by sharing good food with good friends.

Tom Ballard, R.N., N.D., is a naturopathic physician. His book, “Nutrition-1-2-3: Three proven diet wisdoms for losing weight, gaining energy, and reversing chronic disease,” is sold at PCC. Contact him at TomBallardND@gmail.com or PureWellnessCenters.com.