A new era for a small planet

This article was originally published in January 2022

In the 1960s Frances Moore Lappé saw a world paralyzed by fear, expecting global famines and destruction due to overpopulation.

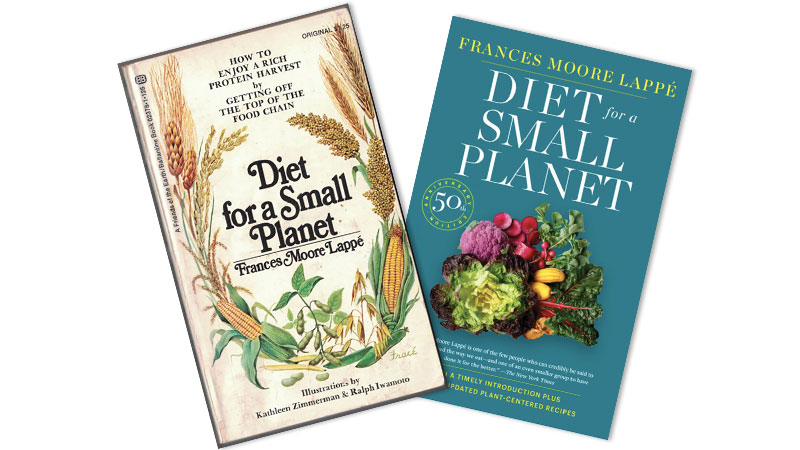

The book the young graduate student researched in response, “Diet for a Small Planet,” dramatically altered the debate—and the way people ate. It also made it clear that nutrition is a matter of economics and politics.

Lappé posed a concept, heretical at the time, that food was abundantly available if we changed entrenched assumptions. By eating plant-centered meals, rather than the inefficient “reverse protein factory” of standard meat production, a brighter future was possible.

In the half-century since “Diet” was first published, Frances “Frankie” Lappé’s original message has become widely accepted—even as the world has faced even more dire threats. And Lappé has kept working on projects, with daughter Anna Lappé in recent years, to meet the challenges of a modern, hotter and even smaller world.

As she wrote bluntly in the revised, expanded 50th anniversary edition, “Either we now make a big turn, or life on Earth as we know it is gone forever.”

Both women spoke by video with Sound Consumer editor Rebekah Denn to mark a revised 50th anniversary edition of “Diet for a Small Planet” that includes new material and new recipes. Here is an edited, condensed version of their conversation:

Q: The times we’re in now are so different than when you first wrote the book—and the book is different. Can you speak to what you want people to get from it now versus then?

Frances: The major thing I took away as a 26-year-old was, I realized that people who assumed scarcity were seeing it. In fact, the truth was that we human beings were creating what we feared. By our economic system, we were denying people power to access the food they needed…

It was always the original view to shift from this focus on quantity, quantity, quantity and scarcity, scarcity, to shift toward what I call a relational worldview. In the opening chapter I quote Hans-Peter Durr, (the late) German physicist who said “Frankie, in biological systems there are no parts, there are only participants.”

Fifty years ago, so many of us were just learning the word ecology for the first time…but what is ecology? It’s all about relationships, right? That is the big shift that makes the message of “Diet” so much more relevant, because then we see that every choice we make—and don’t make—changes the world.

We can’t *not* change the world, we are changing it. And our inaction can be as powerful as our action.

To me that is the huge emphasis in the new version: We are reversing the order of our usual expression “seeing is believing,” and now saying “No, no, no, actually believing is seeing.” If we believe in scarcity, we’ll see it. Whereas if we have a relational worldview, we’re seeing that everything is in constant motion and is being created by our choices.

Anna: As my mother said, what has moved her most about the book has been the conversations she’s had with readers who’ve read the book and said, not just “reading your book changed my diet,” but “reading your book changed my life, you know, it really set me on a different life’s path.”

That to me is a really powerful message of the book, that it isn’t an either/or between what we do as individuals and what we want to see happen on a broader scale.

The piece that I worked on was the second section, the recipes. We wanted to provide space for recipes from people we feel embody the multitude and diversity of people at the leading edge of helping all of us understand how to put plants at the center of our plate, and how to do it in a way that is joyful and delicious. So that was a very conscious choice to invite about 14 people to add a recipe.

Then the second thing we looked to do in Book Two and the updates to the recipes was bring in even more of the diversity of the plant world, of that kingdom.

The third thing we wanted the book to really drive home as people read it and cook from it is the easiness of the diet that Mom has talked about all these years. This isn’t about “You need to go to culinary school to cook for yourself.” This isn’t about some kind of fad diet that requires that you micromanage what you buy and what you eat. This isn’t about obsessing about protein, actually the science tells us it’s really easy to get all the protein we need without obsessing about where you’re getting it from. The multi-billion dollar diet industry has created this narrative that in order to eat healthy, one must be obsessed with our food. When, ironically, that is the least healthy thing to do. We just wanted to showcase recipes that were easy to cook and accessible, and drive home the messaging that eating a diet for a small planet is just, at core, a healthy choice, and you don’t need to overthink it.

Q: The fact that the book has recipes at all is interesting. Usually we see policy presented as sort of hard serious material while recipes are presented as fun stuff. I wonder if that combination is why the book reached so many people.

Frances: I think so. I often say there are very few choices we make multiple times a day…but with food, it’s so satisfying to know that these choices that we’re making have such power.

Another thing I was just thinking about today was the word companion. I learned not long ago it (originates) from the Latin word for bread. There’s something about breaking bread, literally, encouraging people to experience that joy, that’s speaking to something very deep in people’s need for connection.

Q: So much of what you talk about in the book is changing practices that many Americans think of as just the way we do things. In a lot of areas as a society we seem to have trouble saying “maybe our assumptions are wrong” or “maybe the things everyone has always done aren’t actually right.” That seems like a huge mountain to climb.

Frances: There is a lot of awakening going on today in terms of the exposing of the corruption of our democratic process that is answering much more to private wealth than it is to the citizen voters. I was working on something today about the degradation of our food supply that I couldn’t have imagined 50 years ago, that today 60% of our calories come from processed food products. There’s (an) increase in diabetes directly related to that deprivation, and how hard it is for many people to access healthy food, and all that is related to our extreme economic inequality. It’s two directions at once: Yes, there’s this incredible awakening and spreading of the joy of plant-centered (food) and the need for plant-centric eating, for a variety of reasons. At the same time, the dominant culture has gone so heavily into ultra-processed food. It has become a great source of disease.

Q: How do we weight the scales the way that they should go, when so much of the institutional power seems to be on the other side?

Frances: That’s why I have to be always walking on the democracy step and the food movement, you know, that they are inseparable. I always love to point out that in the preamble to our Constitution is that the goal of this nation is to promote the general welfare. Not the individual freedom to do whatever you want, but the general welfare. And clearly a healthy diet is essential, at the very base of our general welfare, so I feel like this is very appropriate, to put it in the framework of democracy. And, really, removing the power of private wealth over the public welfare.

Anna: Yes, and just to give a concrete example of the influence of private interests throughout our governments, I was just looking at some of the reporting about the debates around the 2015 revisions of the U.S. Dietary Guidelines and how much the meat industry lobbied to ensure that the final messaging that the American public heard in those dietary guidelines was not a clear message of “eat less meat.”…The messaging “eat less meat” was impossible for public health advocates to get in there, precisely because of the lobbying power of the meat industry. That’s just one example. There are countless. But the point that my Mom is making now and has been making for decades is that what we see in the outcomes of our food system is a food system that is literally killing us. One in five deaths worldwide, the Lancet’s recent global assessment found, comes from diet-related illnesses. (It also involves) how much private interests are influencing everything from what we hear is a healthy diet to what farmers get incentivized to grow, to what pesticides are allowed to be continued to use in the marketplace, and on and on.

Q: I’m hearing many wise people who have seen a lot who are very depressed right now about the future, and I think you are an exception. You have this list of monumentally depressing things in the book that are threatening our future, but you say we can’t just stay mired in despair. How is that possible when people feel so weighted down?

Frances: I certainly understand how people feel today. And so I’ve returned to this premise I’ve developed, sort of grounding points about what human beings need to thrive, beyond the physical. We need a sense of agency, right? We need to feel that we matter, that we count, that we have power. We need a sense of meaning, that what we do has meaning, and we need connection with others. To me then, crawling in a hole is destroying myself.

To be human is to have some smidgen of sense of possibility. I say a lot that human beings don’t need certainty. All we need is just the possibility that our acts could matter. We can’t be sure that we can turn things around, in terms of the Earth, destruction, the climate crisis, just to take one thread, but…doing something, that I know increases the possibility that we can make this turn toward life. That gives me life, that gives me joy. I just feel that that’s what’s required of all of us, to do that work, to see where is there possibility for change, or is that possibility of influence, if it’s only our neighbors or our children or friends. And to, in a sense, demand for ourselves that we have power. We have a sense of agency, meaning and connection in our lives. That we deserve it, you know, and whatever it takes to get it.

That’s kind of what keeps me going, and also I think that overcoming despair often means doing what you thought you could not do, and taking a risk you thought you couldn’t. And that then makes you believe that other people can change. Because if we get stuck in a hole, and don’t feel like we can get out of it, how can we expect our kids or others to get out of it?

Anna: I live in Northern California. We had 44 days of toxic wildfire smoke-filled air last year where kids were basically not able to go outside. In this moment, I feel like tapping into my joy, tapping into my own happiness, is itself a political act. The fossil fuel industry has already stolen a stable climate from us, the global food industry has already taken away so much of basic human health for so many people, the global chemical industry has already created so many cancers around the world that affect every single one of us… in that context, if in addition, these global industries that have so destroyed the basis on which life exists on the planet, also destroy my ability to wake up and have a good day, to be a good mom…then, you know, they’ve really won. And so there is sort of an activist in me that feels that way about experiencing joy, despite the pain and suffering. Some people could feel like “Well, how can you be happy when the world is on fire? How can you write? How can you not be depressed, doesn’t being depressed show how in touch with reality you are and how clear eyed you are about how big the crisis is?” What I’m offering is kind of another way to think about it. I am not denying how screwed we are, how much damage has been done and continues to be done. Yet part of my sense of my own activism is to still try to put my chin up in the mornings and enjoy the life that I am able to live.

Frances: When I talk, I use that phrase “the act of rebel sanity,” that you’re saying feeling joy and expressing it is a rebellious act of sanity and choosing, that they haven’t taken all of our choices away. And we refuse to allow that.