2020 brings big changes to nutrition label

By Rebekah Denn

This article was originally published in January 2020

Consumers are getting some new tools to help make informed choices about what they eat.

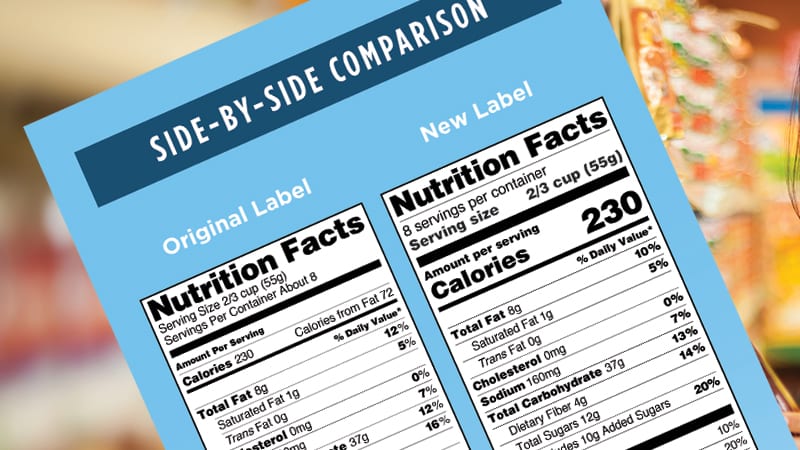

As of Jan. 1, most packaged foods must display a revised version of the Nutrition Facts Label required by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). It’s the biggest change to the standardized label in more than 20 years and will require producers to detail how much added sugar the products contain, among other changes. (Companies with less than $10 million in annual sales have until 2021 to use the new label, but many are already making the transition.)

The redesigned label “will help consumers eat healthier diets,” said Lindsay Moyer, senior nutritionist for the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a nonprofit watchdog and consumer advocacy group.

It’s likely to do that in two ways: It will give shoppers information they didn’t have before, possibly influencing what products they ultimately buy. Manufacturers might then adjust their recipes if they see a greater demand for more healthful products.

The Nutrition Facts Label is a powerful tool and is part of a regulatory process that has slowly evolved since processed foods became more prevalent in the American diet.

“What this panel is supposed to do is take something very complex, food, and a very complex question—‘What should I eat to be healthy?’—and distill it down into something very simple that people can understand without needing a degree in nutrition,” said Charlotte Vallaeys, senior policy analyst for food and nutrition for Consumer Reports, the nonprofit organization dedicated to unbiased consumer-oriented research and public education. A 2016 study by the organization found that 79% of consumers look at nutrition facts on the package when deciding whether to purchase a processed food item for the first time.

The federal government didn’t require such labeling a few generations back, when “meals were generally prepared at home from basic ingredients and there was little demand for nutritional information,” according to a history of nutrition labeling commissioned by Congress and published by the nonprofit Institute of Medicine (IOM).

Information on calories or sodium content was included on some packaged foods after 1941, but that data was meant for people with special dietary needs, not the general population. Even the original 1973 Nutrition Facts Label was optional unless manufacturers had added nutrients to the food or made health claims about it.

By 1989 pressure was rising to require a standardized nutrition label, when evidence-based links between diet and health became clearer and packaged foods strayed farther from whole unprocessed ingredients. Dr. Louis Sullivan, then secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, warned that “The grocery store has become a Tower of Babel and consumers need to be linguists, scientists and mind readers to understand the many labels they see,” according to the IOM history. The panel was finally required as of 1994, under the terms of the 1990 federal Nutritional Labeling and Education Act, which also regulated health claims on labels. The major change since then has been requiring a listing for trans fat.

The current revision was based on further advances in our understanding of food and health.

The FDA received nearly 300,000 comments on proposed changes from all sides of the industry, including 457 form letters from employees of the Ocean Spray cooperative asking that cranberry products (e.g., dried Craisins) be exempt from the added sugar rule, since they are as nutrient-dense as foods with naturally occurring sugars. (The request was declined, but manufacturers may explain on the package that sugars are added for palatability because cranberries are naturally tart.)

PCC Community Markets also commented, applauding the FDA for an update that would provide “valuable information to help shoppers make more informed choices at the supermarket.” The letter stressed that the added sugars label should be required, not voluntary. One of the most important pieces of dietary advice PCC’s nutrition educator can provide, it said, is to follow the American Heart Association’s (AHA) recommendation to consume no more than 5% of calories from added sugars.

“Americans consume a whopping 16% of total calories from added sugars — triple the amount recommended by the AHA and the World Health Organization — but shoppers currently do not have the information available on food labels to make this needed dietary change,” the letter said in 2015.

The process, clearly, moves slowly.

“These things are part of federal regulations, and it takes a long time to make changes,” Vallaeys said. The highly regulated process does have some benefits: “Everyone has to put the same information on the label and has to calculate it in the same way, whether you’re Kraft or Kellogg.”

A remaining limit to the label’s benefits, Vallaeys added, is that it doesn’t provide much interpretation or guidance. For instance, “A nutrient that most Americans should be getting more of (fiber) is listed in the same place and style as a nutrient that most Americans should be consuming less of (sodium), so it’s still not very intuitive.”

That may be an update — or overhaul — for yet another decade.

Here’s what to expect from what the FDA calls “the new and improved nutrition facts label,” with commentary from Vallaeys.

- Calories are listed more prominently.

- Calories from fat no longer have to be listed. This reflects current science that it is the type of fat rather than the amount that is more important.

- Added sugars will now appear underneath the “total sugars” line, helping consumers distinguish between, say, naturally occurring sugars in unsweetened yogurt and added sugars in flavored yogurt. The FDA also established a Daily Reference Value (DRV) for added sugars and will require this to be listed as a Daily Value (DV). The DV for added sugars is set at 50 grams. “That doesn’t mean consumers should aim for 50 grams, but this is an upper limit (and keep in mind other organizations like the AHA have recommendations that are lower than this),” said Vallaeys. She also warns that industries might respond to this change by using non-nutritive sweeteners instead of sugar, the way producers switched to fat replacements like gums in the 1990s. (Unintended consequences could also follow, such as encouraging greater use of ingredients like allulose, a little-known sweetener that has been exempted from the added sugars label. Allulose has not yet been approved for use in the European Union or Canada.)

- Vitamin and mineral listings have changed, and daily values have been updated based on newer scientific evidence. Vitamin A and C are no longer required, since deficiencies of those vitamins are rare today, but potassium and Vitamin D are now required. Quantities must also be listed along with the percentage values, but the label does not make it clear that the daily value might be different for different types of people. “Your individual needs may be very different than what is listed as the daily value percentage,” Vallaeys said.

- Serving sizes have been updated. This is not supposed to be a recommendation for how much to eat, but rather a reflection of how much people are actually eating or drinking at a time. The ice cream serving size went up from ½ cup to 2⁄3 cup, for instance, and a 20-ounce soda bottle is now considered a single serving rather than multiple servings. “Just like the other parts of the nutrition facts label, the serving size is regulated and has to be consistent across products in the same category. This allows consumers to compare products without too much mental math,” Vallaeys said.

- Dual column labels: “For example, if a package has more than a single serving but could be entirely consumed in one sitting, there has to be “dual column” labeling: one column with the official serving size but another for the entire package. I think this is very useful.”

Label lowdown

What can you learn from food labels? What’s the difference between “cage-free” eggs or a “certified humane” guarantee, or “certified organic” versus “made with organic ingredients”? Read the Sound Consumer’s “label lowdown” feature throughout 2020, where we’ll work with Consumer Reports and other expert sources to explain the protections different labels do—and don’t—provide. If there’s a label you’d like us to address, send recommendations to editor@pccmarkets.com.