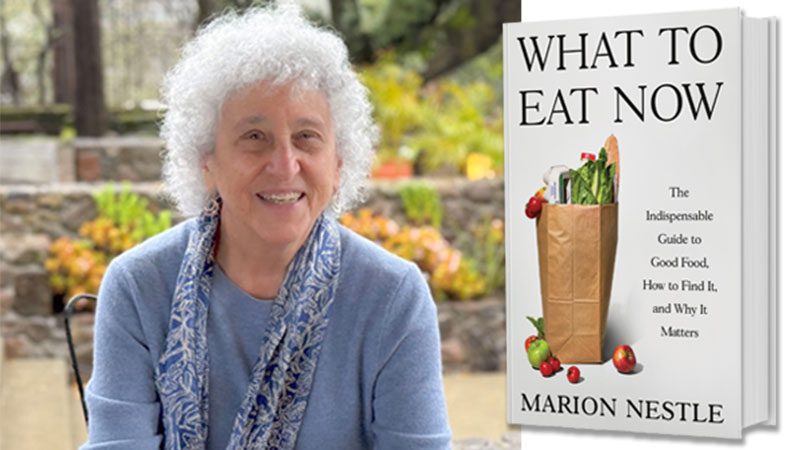

Marion Nestle on “What to Eat Now”

Want to know what to eat — and why? For decades, consumers have relied on Marion Nestle, emeritus professor of Nutrition, Food Studies, and Public Health at New York University, for frank and powerfully informed advice. Nestle, whose long resume includes a stint as senior nutrition policy advisor for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, shares topical insights on policy and marketing in her regular “Food Politics” blog, and her books provide a bedrock education on subjects from skewed science to tainted pet food.

Nestle’s latest release is a complete revision of her 2006 book “What to Eat,” a guide to steering through advertising claims and confusing nutrition advice at the supermarket. The new 720-page “What to Eat Now” covers more recent seismic changes in the industry — and the world.

Nestle, 89, recently spoke with Sound Consumer editor Rebekah Denn about the book, about modern food politics, and that fundamental question — what to eat? Here are edited, condensed excerpts from the conversation.

Q: I have to start by thanking you for your original “What to Eat.” When my oldest child started eating solid food, I was feeding him flavored baby yogurts for lunch. It was organic, it was for babies, I thought I was being so good! Then I read your book and saw I should think of it as dessert instead of a meal because of all the added sugar. So I started thinking of it as a dessert — and I started paying more attention to all these issues.

A: Thank you. I wish I had known all that when my kids were little.

Q: What has changed so much that it called for a completely revised “What to Eat”?

A: The big changes are ultra processed foods, online ordering. Plant based foods — that’s a whole new category of foods that really didn’t exist 20 years ago, except for soy milk. The enormous replacement of full sugar beverages with waters of one kind or another. The introduction of cannabis. The enormous influx of international foods into not only its own section, but throughout the supermarket. And then, the issues have been updated: There are new laws, there are new regulations, there is new labeling.

I just couldn’t believe how much there was, and it took a very long time to get it all in there.

Q: What surprised you the most?

A: The online ordering. I walked into a Wegmans in Ithaca one day and I couldn’t find anything. The store had been completely reorganized, and so shockingly that I went to talk to the store manager about what happened. He said, “Well, we had to make space for where we’re going to stock the bags (for online order pickups).” And that space had been occupied by beer. Beer is an enormous, absolutely enormous fraction of supermarket real estate in that particular Wegmans, but they had to find another place for it, because that was the section that was close to the parking lot. In order to do that, they had to reorganize the entire store.

Q: Has it gotten easier or harder to get the information you need for your work?

A: A lot of the websites that I used as references are gone. Now the government isn’t producing that kind of data.

Q: What’s the impact going to be?

A: People like me are going to find their work much harder. I will be much more dependent on reporters who have sources of information that I don’t for digging up that kind of thing. (But) this is not the first time the Department of Agriculture stopped producing a database that I used every year. It stopped producing one in 2010, and I complained. What I was looking for was the number of calories available for consumption in the food supply on a per capita basis. I said, “This is data that you have kept on food availability in the food supply since 1909. Why are you stopping it 100 years later?” Basically, they said “You’re the only one who uses it.” I found that very hard to believe.

Q: Reading the book, I felt like seafood was an area where it is unexpectedly hard to make an informed choice.

A: The Wild West of the supermarket, yes. The fish chapters were so complicated, and there is so much information in them, they were also published as a separate book, called The Fish Counter.

You have to rely on your fish seller, because there’s no third-party certifier that covers all of the issues that I care about. (Editor’s note: See PCC’s seafood standard here and Chinook salmon standard here.) There are third party certifiers for sustainability and for some other issues, but not for all of them. The Monterey Bay Aquarium has probably the most widely circulated third party certifier of fish, but I don’t think it covers safety, doesn’t cover methylmercury, doesn’t cover PCBs. And if you want to know this stuff — and I do — you’re kind of stuck.

Q: Almost everything seems to come down to putting the responsibility on individuals to be informed on some really complicated things.

A: I tried to show in the book what you have to go through to become informed. If you’re starting out, you have to know a lot. And with fish, you have to know what the fish is, what the species is, what its life cycle is, where it was caught, what time of year it was caught, under what circumstances was it caught, how was it treated afterwards… How are you supposed to know this? Government agencies put out a safety list for 60 different fish. Who knows the difference between 60 kinds of fish?

You asked what surprised me. One thing was that you cannot eat fish from local waters practically anywhere in the United States (because of contamination). That just seems unconscionable to me.

Q: One of your signature issues is industry marketing to children. You wrote about how you were at a White House event, and someone in the industry told you, “We’d love to stop marketing to kids, but our shareholders won’t let us.”

A: The most blatant statement about the power of the shareholder value movement that I had ever heard. Well, that’s putting profits over public health, as clear a statement of it as I’ve ever seen.

Q: Are there any general, simple rules to eat by?

A: I think eating is so simple. You know, Michael Pollan, seven words: “Eat food, not too much, mostly plants.” All you have to do is modify “eat food” and explain that by food you’re talking about minimally or unprocessed foods,

The concept of ultra processed foods, which only came out in 2009, has been a very useful concept. It’s a specific category of junk foods that has been shown in hundreds, literally hundreds of studies, to be associated with poor health if you eat a lot of them — and in a few very, very well controlled clinical trials, has been shown to encourage people to eat more calories. So a very simple rule of eating is “don’t eat too much ultra processed food.” Not none. I like my share of ultra processed foods, I just try not to eat too much of them.

Q: Defining processed foods seems also complicated.

A: There’s a big fuss about the definition of ultra processed foods, but I think everybody knows what they are. We can probably define them better, but in general, they’re industrially produced. You can’t make them in your home kitchen because you don’t have the additives, or you don’t have the equipment. They generally have a lot of ingredients, and many of those ingredients are things that you don’t have access to, they’re industrially produced ingredients. So you want to eat food that looks like food, the way it was raised.

Q: In an ideal world, have you thought about what dietary guidelines you would want to see?

A: I think the dietary guidelines are very simply “Eat food, not too much, mostly plants.” So I would like to see food-based dietary guidelines: “Eat a wide variety of food, of as many different kinds as you possibly can every day, but in very small amounts, because they add up.”

It’s possible to eat healthfully in uncountable numbers of ways, if you’re eating minimally processed foods and not eating too much of them. It’s that simple — and that it seems so complicated, and makes people so unhappy, has to do with the food marketing environment, which is set up to get you to do anything but “eat food, not too much, mostly plants.”

The purpose of a food company is to sell more food, not less, and please those stockholders. And in order to do that, they have to get you to eat too much of the most profitable foods.

Q: I’ve been surprised recently by the vehemence against seed oils, how convinced many people are that they are bad. It’s even more forceful than objections to high-fructose corn syrup years back.

A: There are two grains of truth in the argument. One is that the consumption of seed oils increased in parallel with obesity, and obesity is a risk factor for chronic diseases — but the consumption of everything increased in parallel with obesity.

And, seed oils can get rancid. The more unsaturated they are, the easier it is for them to become rancid. So you want to keep the seed oils in dark bottles, and if they’re highly unsaturated, you want to keep them in the refrigerator and be careful about them.

But the rest of it flies against the face of the science that we know. We know that substituting seed oils for solid fats, the ones that are highly saturated, reduces blood cholesterol levels and the risk of heart disease. That research has not changed.

It’s like the push of “Let’s substitute cane sugar for high fructose corn syrup,” which I can’t even say without laughing, because basically they’re identical biochemically.

The current people who are in political power have some very strange ideas about nutrition, and they seem quite locked in on them. We’ll see what the new dietary guidelines say. I can’t wait to see them.

Q: The MAHA movement has put a lot of changes you have supported for a long time to the forefront of public discussion.

A: Yes, it’s been really exciting.

Q: Do you think changes are coming?

A: Well, I’m not seeing the ones that I’m interested in. The MAHA wins are largely restricted to companies who have voluntarily agreed to remove artificially colored dyes from their products. Great. I’m in favor of that. Is it going to make a difference to the health of America’s children? I think not very much, because Froot Loops with vegetable dyes are still Froot Loops. It doesn’t change anything fundamental, but it’s nice for kids who might react to color dyes.

There are two others: One is, Coca Cola has said it will substitute cane sugar for high fructose corn syrup — which I still can’t say without laughing — and the other one is that the FDA is going to change its regulations on what additives can be considered “Generally Recognized as Safe,” and that’s been a long time coming. That’s a good thing. But the really important ones, the fundamental ones, they’re not doing anything about. They’re not doing anything about marketing junk food to children. They’re not doing anything about ultra processed food other than defining it. Maybe that’s the first step, but they haven’t said what they’re going to do once it’s defined.

Q: I was very struck in the book when you talked about the increasing inability of government to create guidelines that just say what they mean — how in 1980, I think, they said “Don’t eat too much sugar,” but by 2020 political pressures made that same guideline just a mishmash.

A: One of the things (U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services) RFK Jr. has promised is that these guidelines will be five pages, and presumably they’ll remove the obfuscation. I will believe it when I see it. I look forward to seeing them.

Q: Can you talk a little about why you support eating organic foods?

A: Why I favor organic certification is that it is federally mandated. It comes with a lot of rules and regulations that organic producers are supposed to follow, and there’s a monitoring system to make sure that they do. There are problems with it, but most people I know think it’s working pretty well. And certainly the organic producers that I meet think that it really holds their feet to the fire, and they work really, really hard to make sure that they’re doing what they’re supposed to be doing.

There are now things like the Real Organic Project, which is trying to add regenerative practices to the organic certification, but it’s built on top of the organic certification, sort of like “organic plus,” and that seems like a good way to proceed.

Organic is about production values. It’s about producing foods in ways that don’t detract from soil. (Organic crops) are not allowed to be fertilized with sewage sludge, for example. That was smart. Now that we’re seeing that there are whole areas of farmland that are being ruined from being fertilized with sewage sludge, you could see how smart the organic community was in getting that rule put in there. They’re non-GMO, whether you care about that is another matter.

I think the rules are fine. I wish they were even more rigorous than they were. I wish that the Organic Standards Board would fight to the death to keep those standards high. Big organic producers want the standards reduced as much as possible so they can count their stuff as organic, while not having to do all those expensive procedures. And I wish the government would subsidize it so it didn’t cost so much.

Q: Are subsidies the only way to get organics to a more affordable point?

A: Right now the foods that are subsidized are corn and soybeans, mainly. Nearly half of them go to feed animals. The other half goes for ethanol or other kinds of biofuels. That’s just crazy. We’re using farmland for biofuels. Why aren’t we growing food for people? We should have an agricultural system that is focused on feeding people healthy food. That would make a big difference.

Q: Do you think about climate change in terms of how we can eat, or should eat?

A: Beef is the single food with the greatest impact on climate change. If you want to do something about climate change, that’s the first thing you do. You eat less beef, not necessarily none, but certainly less.

Q: Your newsletter regularly reports on research studies that are industry-funded, and you point out that the results are no surprise. Have you seen any game-changing research lately?

A: Oh, absolutely. In a way, what you’re saying — or what I’m doing (with the newsletter) — is a little unfair, because I’m only looking at industry funded studies. Occasionally I will find an industry funded study with a result that doesn’t favor the sponsor, and I’ll talk about that. Those are pretty rare, but I’m focusing on industry funded studies because they are so obvious. I can look at the title and figure out who paid for it and if I know who paid for it I know what the results are going to be. There’s something wrong with that picture, but that’s what I’m emphasizing. I do one of those a week, usually.

But the studies on ultra processed foods I think are the most important nutrition studies that have been done since vitamins. These are the controlled metabolic studies done by Kevin Hall and his colleagues at NIH — they’ve now been repeated in a couple of other places — that show ultra processed foods encourage people to eat more calories than they otherwise would. And not just a few more calories, hundreds more calories. In the case of the study at NIH, it was 500 more a day on average. In the case of the one that was done in Japan, it was 800 more on average, and another one shows 1000 more on average. And even when the foods are supposedly healthy and are somewhat less processed, like whole wheat breads or kids yogurts, people eat more calories than they would from relatively unprocessed foods.

I think that’s a profound observation, and it tells you really simply, if you don’t want to gain weight, don’t eat ultra processed foods, or, at least, don’t eat very much of them.

Q: Everyone reads you. But who do you read, who do you rely on for information?

A: Everybody. I read absolutely everybody. I probably get 20 or 30 newsletters a day from people who are writing about food. There’s a set of newsletters from Europe, I get about 10 of them. I read Food Fix, Helena Bottemiller Evich’s newsletter from Washington. I read The Hagstrom Report. I read people who are writing about what’s happening in Washington, because I don’t have access to what’s happening in Washington. I read academic journals, I read newspapers. At this point, I get sent stuff a lot, and I read it and try to put it together in some meaningful way or way that makes sense.