A Love Letter to Nabe, Japan’s Winter Hot Pot

By Tara Austen Weaver, guest contributor

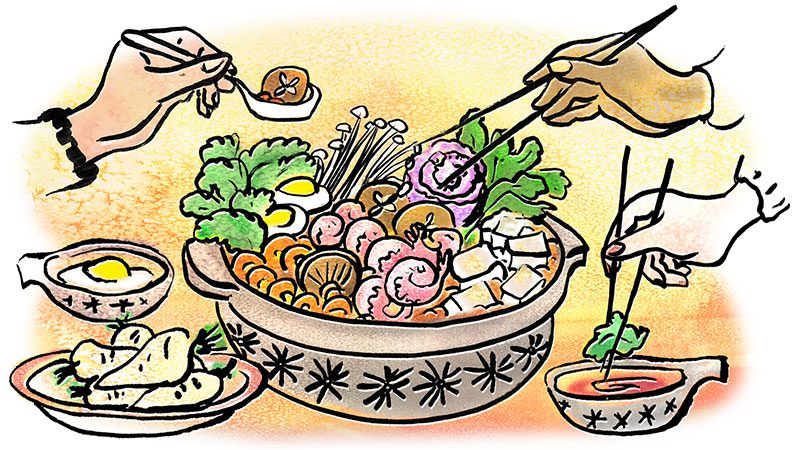

Illustration by Wendy Wahman

When winter rolls around, some people devote themselves to the virtues of kale and green tea, as if to atone for holiday merriment. Others grab a soup ladle and declare they will simmer their way through the season. I have a different approach. I pull out the nabe pot.

What is nabe? It is Japan’s answer to seasonal doldrums and hunger pangs. If you ask me, it might be the best thing about winter.

I was introduced to this Japanese hot-pot style of cooking the night I arrived in my new home high in the mountains of central Japan. A freshly graduated college student, I was to live with a family for four months. That first night, a large clay pot with a domed lid sat in the center of the table. When opened, it revealed a steaming cauldron filled with fish cakes and chunks of carrots, potato, daikon radish, and peeled hard-boiled eggs—all simmering in a rich soup broth.

Each member of the family dipped into the communal pot with a clay ladle to spoon out their favorite items. It was warm and convivial—and, by the end of the evening, both my belly and my heart felt full. If ever a meal felt like a cozy hug, nabe is it.

The origins of nabe

The origins of nabe cooking go back generations, to when Japanese homes were heated by an open hearth over which hung a cooking pot full of broth, vegetables, and fish. The pots are called “donabe” (clay pot) and come in a variety of sizes. While nabe is often made for a family or a crowd, you can also make nabe for one or two people. My favorite easy nabe recipe consists of leeks, napa cabbage, carrots, tofu, and mushrooms with a tangy ponzu dipping sauce. It’s clean, simple, and comforting.

But nabe cooking runs the gamut—with certain areas in Japan known for one style or another. In far north Hokkaido, where salmon is plentiful, Ishikari nabe poaches the fish in a broth of miso with vegetables. The port city of Hiroshima is known for Dote nabe, which features fresh oysters. Sumo wrestlers feast on Chanko nabe, which is chock full of chicken, beef, pork belly, and vegetables. There are restaurants, helmed by former wrestlers, where you can eat like the Sumo on Chanko nabe.

I didn’t know it then, but the fishcake stew I enjoyed that first night with my Japanese host family is called oden. It’s so popular that all winter long there is a vat of oden simmering away at convenience stores throughout the country. On a cold day, it is such a treat to wrap your hands around a warm bowl of this seasonal comfort food, the richness of the broth cut by a sharp dab of mustard on the side.

Nabe has even entered the realm of fusion cooking, with the highly popular Kimchi nabe—which features tofu, vegetables, and pork, beef or seafood in a fiery red broth with the added tang of Korean pickled kimchi.

The best-known nabe

Perhaps the most well-known of all nabe, particularly outside of Japan, is sukiyaki. It is a mixture of thinly sliced beef, leeks, chunks of tofu, mushrooms, carrots, and other vegetables simmered in a slightly sweetened sauce of soy and sake. The traditional way is to take the piping hot ingredients out of the cooking pot and dip in raw egg before eating, but this custom does not often leave the country.

The truth is that nabe itself does not often leave Japan. Though you can find the dish in restaurants, it is mostly a staple of home cooking—served at least weekly in winter. Nabe is an easy, nutritious, and filling meal that helps clear the contents of a vegetable bin and keep spirits up in cold and gloomy weather.

Nabe is also tableside entertainment. You can assemble the hot pot ingredients and cook the nabe before bringing it to the table, or you can put out platters of raw ingredients and allow guests to add to the pot as the meal goes on. Most Japanese homes have at least one portable burner to facilitate tabletop simmering.

As the meal goes on, the broth gets richer and richer with each addition of vegetables or protein. The final stage of nabe consists of adding some starch—either rice or noodles, often udon—to soak up and simmer in this flavorful liquid. Sometimes an egg is also added, to make a savory sort of rice porridge. It’s the perfect end to such a satisfying meal.

Nabe may not make it onto the menu of many overseas Japanese restaurants, but that doesn’t mean you can’t make it at home. While a big clay nabe pot is nice, it’s not essential. Any pot or braising dish with fairly low sides will work fine (sukiyaki is traditionally cooked in a low sided cast iron pan, preferred for ability to conduct heat).

As the gloomy weather descends, and holiday indulging is in the rearview mirror, why not pull together a pot of steaming and satisfying vegetables, tofu, and meat or seafood? Why not gather friends—or a more intimate group—around a simmering pot of warmth, good food and good cheer? Spring is a way off still, let’s get cozy and tuck in.

Make kimchi nabe at home

Kimchi Nabe

Serves 4

This nabe adds spicy Korean kimchi to a fiery broth with thinly sliced pork, various mushrooms, vegetables, tofu, and chewy udon noodles at the end. It’s a delicious way to warm up a winter’s night. Add vegetables according to your preferences or the contents of your fridge.

The broth for kimchi nabe is often made with a packaged base called kimchi no moto (available at most Asian grocery stores). You can also make it with a mixture of miso and gochujang pepper paste, as outlined below.

8 cups nabe broth (recipe below)

2 tbs brown or red miso

3-4 tbs gochujang pepper paste, according to taste and preferred heat level

1 medium daikon radish, peeled and cut into ½-inch cubes

1 medium to large napa cabbage, about 2.5 pounds

14-ounce package of shirataki yam noodles

½ pound of mushrooms: shiitake, trumpet, enoki, or a mix

2 medium carrots, cut on a diagonal into ¼ inch slices

2 thin leeks or Japanese negi, cut on a diagonal into ¼ inch slices

4 cups kimchi (32-ounces)

2 pounds very thinly sliced pork (Asian grocery stores mark this as “hot pot” meat)

2 14-ounce packages of tofu

1 pound of leafy greens: edible chrysanthemum leaves (called kiku or shugiku), spinach, or garlic chives (called nira), according to taste

20-ounces (approx) fresh udon noodles

In a large pot or clay nabe, add the nabe broth and set over a medium heat. As the broth warms, add the kimchi no moto or miso/gochujang mixture and stir to dissolve. Add the daikon radish and let simmer 10 minutes.

Cut the napa cabbage lengthwise in half and remove the core. Starting at the base, slice the lower portion into ¼-inch strips. The upper, leafier portion can be cut into ½-inch strips. Add the thinner strips to the pot and simmer 5 minutes.

Cut a star shape into each of the shiitake mushrooms, to help them cook evenly, and cut any trumpet mushrooms into ½-inch slices. Add half the mushrooms, skirataki noodles, and carrots to the pot and let simmer another 10 minutes.

Add half the leeks, kimchi, pork, and tofu, cover the pot and simmer another 5 minutes. Add half the greens and cover the pot again, to let the greens wilt, about 5 minutes.

Arrange the remaining ingredients on a platter and bring to the table. Let your guests serve themselves, and add ingredients, according to their preferences. When the soup pot empties out, add the udon noodles and let them cook until soft.

Nabe Broth

Most nabe dishes start with dashi—the classic Japanese stock of kelp (konbu) and shavings of bonito tuna (katsuoboshi). You can buy dashi mix in stores that have a good selection of Asian ingredients, but it is easily made and the ingredients have a long shelf life. If you choose to use a prepared mix, follow the directions on the package before adding the soy sauce, mirin, sake, and salt.

8 cups water

4-inch by 10-inch piece of konbu (kelp)

⅓ cup (10g) katsuobushi flakes

4 tbs soy sauce

4 tbs mirin

4 tbs sake rice wine

1 tsp salt

Pour the water into a large saucepan and add the konbu. If possible, allow the seaweed to soak for up to two hours before proceeding.

Set the water and konbu over medium heat and simmer for about 10 minutes before turning off the heat. Do not allow to boil. After 10 minutes, remove the konbu, add the katsuobushi flakes, and let sit for 10 minutes before straining the dashi. Do not press the solids to extract extra liquid.

Add the soy sauce, mirin, sake, and salt, and stir to incorporate.

Note: you may save the konbu and katsuobushi for a second, slightly less flavorful, batch of stock called number two dashi.